A.1 Fossil Fuel Resource Development Projects. 8

A.2 Indigenous Communities. 11

A.3 Standard Social Impact Assessment (SIA) 15

A.4 Inadequacy of SIA Content 18

A.5 Inappropriateness of SIA Process. 21

A.6 SUMMARY OF THE CCIA PROBLEM… 23

B. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF CCIA METHODOLOGY.. 25

B.1 Theory Of Science And Knowledge Processes. 26

B.2 THEORY OF SYSTEMIC CAUSATION.. 28

B.3 THEORY OF SUBJECTIVE REALITY CONSTRUCTION.. 31

B.4 THEORY OF CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE PARADIGMS. 35

B.5 IDEAS ON THE NATURE AND STUDY OF IMPACTION.. 42

B.6 SUMMARY OF THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK.. 48

C. THE CCIA RESEARCH PROCESS. 53

C.1 Community-Proponent Liaison. 55

C.7 Assessment and Mitigation. 82

C.8 Summary of the CCIA Research Process. 84

Original TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

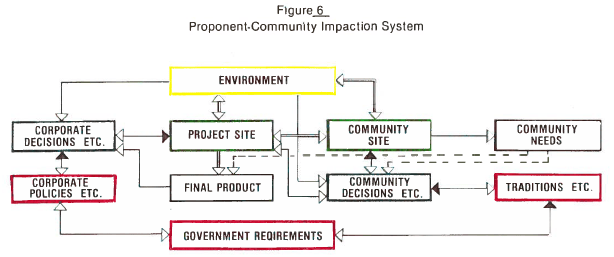

- Cybernetic System — 64

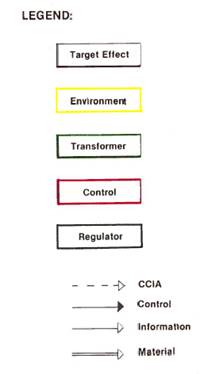

- Intrasystem–Intersystem Interactions — 66

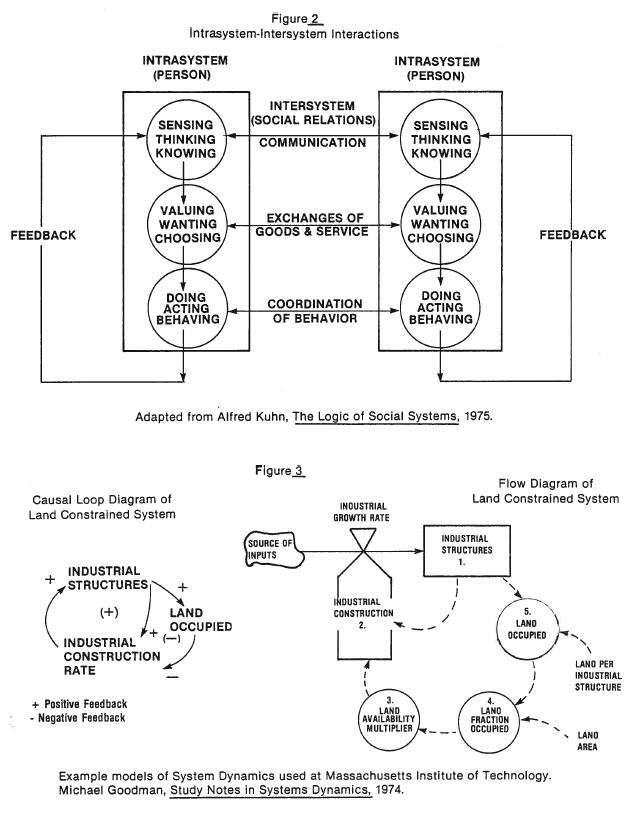

- Causal Loop and Flow Diagrams of Land-Constrained System — 66

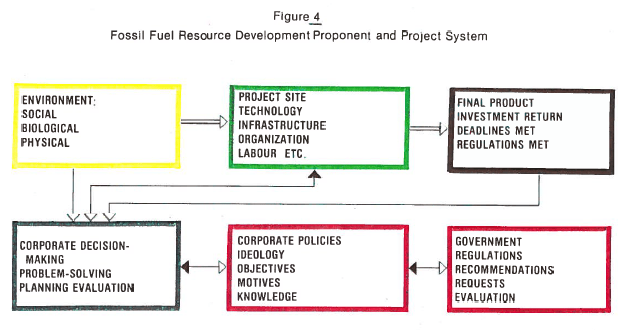

- Fossil Fuel Resource Development Proponent and Project System — 103

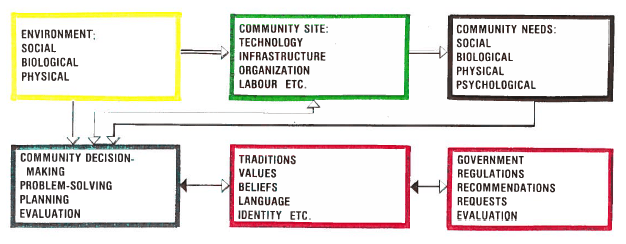

- Indigenous Community System — 103

- Proponent – Community Impaction System — 104

- Inputs and Outputs of Cooperation — 106

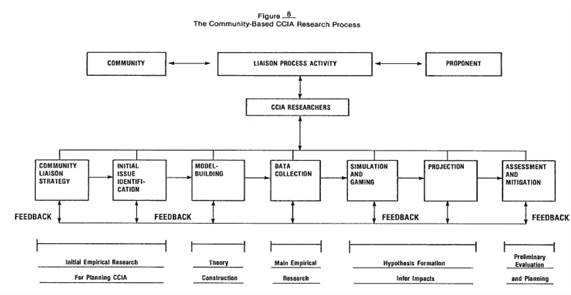

- The Community-Based CCIA Research Process — 118

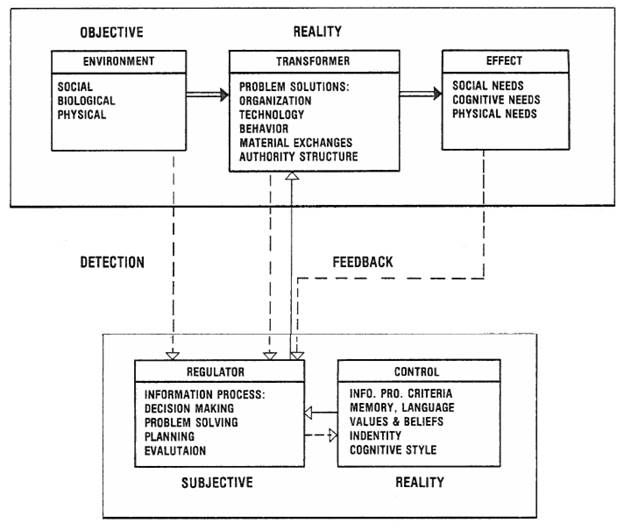

- Socio-Cultural Cybernetic System — 203

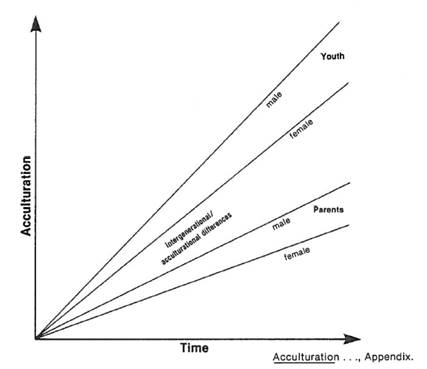

- Acculturational Differences: Age and Sex — 204

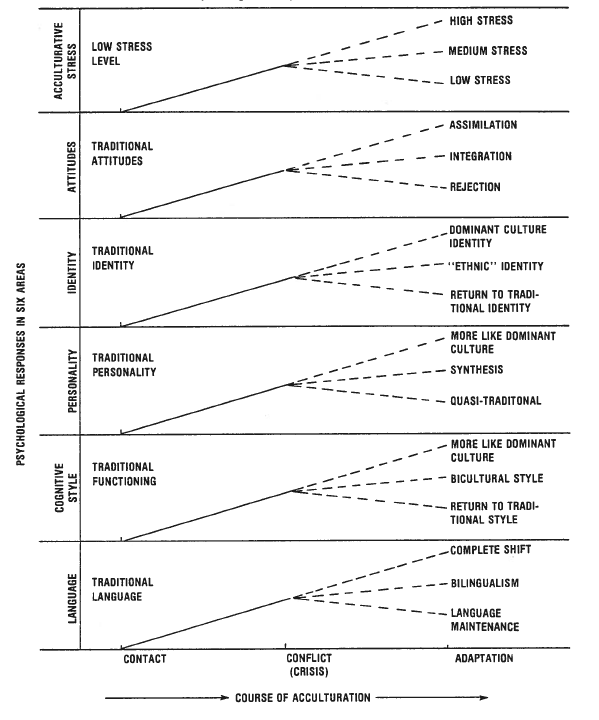

- Six Psychological Response Areas in Acculturation — 205

- Models Increasing in Specificity — 207

- Models Increasing in Complexity — 207

- Graphs Illustrating Trends Caused by Feedback (Examples) — 208

- Positive and Negative Feedback System for Simulation — 208

- Kwakiutl Cultural System — 209

- Cultural Ecology Systems Model — 210

- Example of Process Box for Cultural Perspective Paradigm Simulation — 211

- Example of Stages for Simulation of Cultural Perspective Paradigm — 211

- Example of Processes in a Stage for Simulation of Cultural Perspective Paradigm — 211

- Cultural Perspective Paradigm Model — 212

- Model of Socio-Cultural System — 213

LIST OF TABLES

- Contributions and Rewards of Cooperation — 106

- Acculturation Types (Examples) — 204

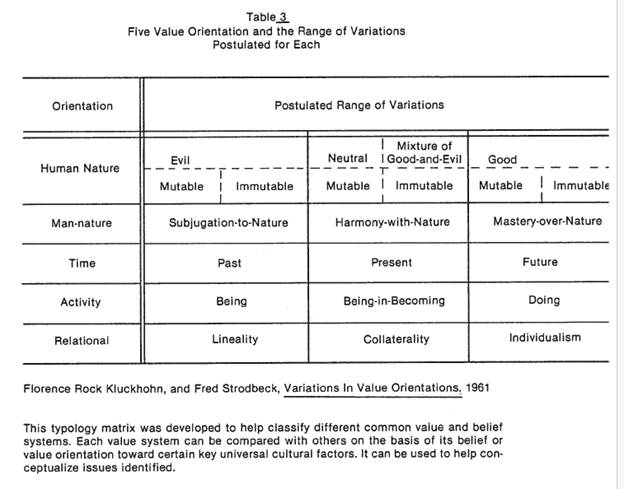

- Five Value Orientations and the Range of Variations for Each — 206

- Selected Data Collection Methods — 214

MAPS

- Ecological Regions of Canada — i

- Approximate Distribution of Major Indigenous Groups When First Contact Made by Whites — ii

- Indian Treaties of Canada — iii

ORIGINAL MAIN CONTENTS

- Executive Summary — iv

- Preface and Acknowledgements — viii

- Introduction — 1

A. Cross-Cultural Impact Assessments: An Introduction to the Problem and the Solution — 6

- Petroleum Resource Development Projects — 8

- a. Impacts — 8

- b. Corporate Objectives — 10

- Indigenous Communities — 14

- a. Diversity of Groups — 14

- b. Traditional Group Similarities — 15

- c. Culture: Two Realities — 18

- d. Subjective Culture — 19

- e. Indigenous Community Development — 22

- f. Acculturation — 24

- Standard Social Impact Assessment (SIA) — 26

- a. SIA for Whom and For What? — 26

- b. Actors and Their Roles in SIA — 29

- c. The Process…Briefly — 30

- Inadequacy of SIA Content — 33

- a. Cultural Differences — 33

- b. Quantitative – Qualitative Differences — 35

- c. Non-Disciplinary Conceptual Framework — 35

- d. Patterns of Causation — 37

- Inappropriateness of SIA Process — 42

- a. Cross-Cultural Communication — 42

- b. Analysis of Subjective Reality — 43

- c. Rapid Acculturation — 45

- d. Diversity of Indigenous Communities — 46

- Summary of the CCIA Problem — 47

B. Theoretical Framework of CCIA Methodology — 51

- Theory of Science and Knowledge Processes — 55

- a. Steps of Scientific Thought — 55

- b. Levels of Knowledge — 57

- c. Examples of Use — 60

- Theory of Systemic Causation — 62

- a. Real and Conceptual Cultural Subsystems — 62

- b. What is a System? — 65

- c. The “Holistic” Community System — 69

- Theory of Subjective Reality Construction — 72

- a. Perspective — 72

- b. Study of Subjective Reality Construction — 74

- c. Insiders and Outsiders — 76

- d. The Symbol System — 78

- e. Cultural Identity — 80

- Theory of Cultural Perspective Paradigms — 82

- a. What is a Cultural Perspective Paradigm? — 83

- b. The Cognitive Dimension — 85

- c. Cognitive Process Rules — 86

- d. Cognitive Process Criteria — 87

- e. The Evaluative Dimension — 91

- f. Evaluative Process Rules — 91

- g. Evaluative Process Criteria — 94

- h. Behavioural Styles — 97

- i. Personality — 98

- j. Summary — 99

- Ideas on The Nature and Study of Impaction — 101

- a. Feedback Interaction — 102

- b. The Subjective Perspectives — 107

- c. Acculturation — 108

- d. The Role of Knowledge and Value — 109

- Summary of the Theoretical Framework — 112

C. The CCIA Research Process — 116

- Community – Proponent Liaison — 119

- a. Considerations in a Strategy — 119

- b. Cross-Cultural Communication Approaches — 120

- c. Community-Based Research — 122

- d. Liaison Methods — 125

- e. Communication Techniques — 126

- f. Summary — 127

- Issue Identification — 128

- a. Research Issues — 128

- b. Issue Organization — 130

- c. Methods of Issue Identification — 130

- d. Summary — 133

- Model-Building — 135

- a. Steps of Model-Building — 137

- b. Purpose and Use of Models — 138

- c. The Subject of the Model — 140

- d. Typologies — 147

- e. Summary — 150

- Data Collection — 151

- a. Levels of Measurement — 152

- b. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analysis — 156

- c. Bias — 157

- d. Valuable Data — 160

- e. Continuous Collection — 162

- f. Summary — 164

- Simulation and Gaming — 166

- a. An Example Simulation — 166

- b. Simulation Building — 169

- c. Criteria of a Good Representation — 171

- d. Gaming — 174

- e. Ongoing Adjustments and Fine Tuning — 178

- f. Summary — 180

- Projection — 182

- a. Aims — 183

- b. Making Projections — 184

- c. Gaming — 185

- d. Computer Use — 186

- e. Criteria of a Good Projection — 187

- f. Summary — 188

- Assessment and Mitigation — 190

- a. Continuous Output Data — 190

- b. The Final Assessment Statement — 193

- c. The Role of Assessment in CCIA Research — 194

- Summary of the CCIA Research Process — 196

Conclusions — 197

- a. Community-Based Assessment — 198

- b. CCIA as a System — 200

- Appendix — 203

- Bibliography — 216

Introduction

Cross-cultural impact assessment (CCIA) is in a formative stage of development. It is evolving to meet requirements demanded by situations of rapid acculturation, particularly as fossil fuel resource development impinges on the lives of Canada’s Indigenous people. CCIA is emerging as a special and unique adaptation of standard social impact assessment (SIA).

As it emerges and evolves, researchers doing CCIA must be aware of the purpose and specific nature of CCIA. They must be able to see its potentials and limitations in describing, explaining, predicting, and controlling cross-cultural impacts. Researchers should also be aware of the body of social science theory which supports CCIA, defines it, and makes it possible. The processes involved in conducting CCIA research should be understood as the main substance and activity of CCIA.

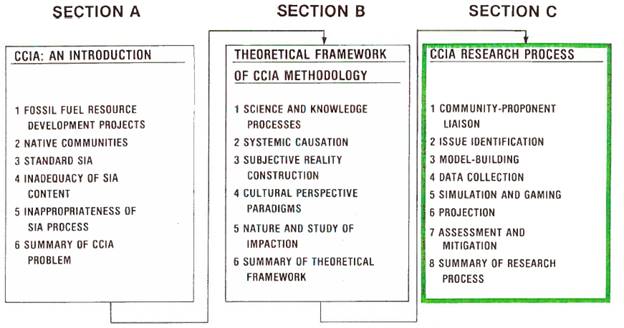

To achieve this understanding, this report is divided into three sections:

A. CCIA: An Introduction;

B. Theoretical Framework for CCIA Methodology; and

C. The CCIA Research Process.

The first section deals with questions concerning the purpose and setting of CCIA; who is involved and in what ways; and required modifications to SIA in the cross-cultural situation. It is argued that for assessing impacts to Indigenous culture caused by fossil fuel resource development projects, standard SIA topical content is inadequate and its research process methods are inappropriate, as they stand. Modifications are needed to address more fully the study of the Indigenous subjective culture (values, beliefs, identity, language, etc.). Changes to the research process involve a more intensive and extensive community participation program, and more comprehensive modelling and simulation than is common in SIA.

The theoretical framework for CCIA methodology points out various considerations in doing CCIA research. The Indigenous community and culture are viewed as an interpersonal information processing system. The way in which local people construct their representations of reality is different from the way other groups construct their realities. The local perspectives shared among residents constitute a cultural perspective paradigm and are to be studied as a whole system of inter-related causes and effects. A scientific thinking process is discussed which is to serve as a basis for thinking in the actual research process.

The relationship between resource development project and Indigenous community is also discussed as a background to the subject to be researched.

The CCIA research process consists of seven stages:

- Community–proponent liaison

- Issue identification

- Model-building

- Data collection

- Simulation and gaming

- Projection

- Assessment and mitigation

Each stage is developed in terms of the purpose, methods used, problems encountered, relationships to other stages, and the nature of subjects studied. Stress is put on the community-based nature of the research and the flexibility required to accommodate uncertainty in the process.

Special note should be made of the fact that this report presents only one range of possible approaches to studying cross-cultural impacts. It is an approach that is very adaptable as it can be used to produce information of any desired complexity or simplicity. If time, money, or professional resources are short, simple models and simulations can be built. If more complete and reliable projections and assessments are needed, complex models and simulations can be built. It can also be changed on the location to suit needs and resources available as they arise.

The report is an attempt to integrate various scientific and humanistic ideas and perspectives to be used with an end to minimize negative impacts and maximizing positive impacts to Indigenous culture. It is not a study of cross-cultural impacts, but a proposal for how such a study can be constructed and carried out.

It is not a study of impacts to the development proponent, although acculturation and impaction are two-way streets. Impacts to the proponent (corporate organization, policy, ideology, and project development) must remain the topic of other reports. However, it is important that CCIA be conducted for the proponent corporation so that it can respond best to the demands of cross-cultural interaction. A cooperative mutual learning centre should be established on the community or project site to facilitate maximum understanding of the rapid acculturation.

CCIA Report Structure

| Section A | Section B | Section C |

| CCIA: An Introduction | Theoretical Framework of CCIA Methodology | CCIA Research Process |

| 1. Fossil Fuel Resource Development Projects | 1. Science and Knowledge Processes | 1. Community–Proponent Liaison |

| 2. Indigenous Communities | 2. Systemic Causation | 2. Issue Identification |

| 3. Standard SIA | 3. Subjective Reality Construction | 3. Model-Building |

| 4. Inadequacy of SIA Content | 4. Cultural Perspective Paradigms | 4. Data Collection |

| 5. Inappropriateness of SIA Process | 5. Nature and Study of Impaction | 5. Simulation and Gaming |

| 6. Summary of CCIA Problem | 6. Summary of Theoretical Framework | 6. Projection |

| 7. Assessment and Mitigation | ||

| 8. Summary of Research Process |

Here’s a polished draft of Section A.1 – Fossil Fuel Resource Development Projects, with subsections Impacts and Corporate Objectives fully merged and lightly cleaned for readability while preserving the original meaning and tone:

A.1 Fossil Fuel Resource Development Projects

Petro-Canada’s main interest is to develop fossil fuel resources in order to make money and serve the Canadian public through the economy. To do this requires finding resource reserves, getting the resource out of the ground, transporting it to refineries for processing, processing it, and transporting the product to consumers. At various stages along the way, development projects (seismic exploration, drilling, pipelines, refineries, etc.) come into contact with Indigenous communities. These are often in the hinterlands of northern Canada but also occur near southern urban Canadian centers.

These projects may be temporary, such as exploration activities, or they may be long term, such as wells, pipelines, or refineries. In either case they may have long-term consequences for local ecologies and Indigenous cultures.

A.1.a Impacts

Impacts are changes made to a community as a result of these kinds of activities. They are not initiated by the community but are caused by the activities of a development proponent. The impacts or effects of these projects may be due to direct cross-cultural contact—as in employment, education, or infrastructural development (roads, houses, sewers, services)—or indirect effects, such as environmental changes caused by projects.

For example, fishing can be affected by refinery effluents, hunting by air traffic noise, and farming by roads and land clearance.

Impacts can be perceived in two ways: either positive or negative. Local residents often disagree about which they are. Some Indigenous people may prefer to maintain traditional educational practices, while others may wish to learn trade skills for wage employment. Often compromises are required.

Employment opportunities are often made available to local residents first, with on-the-job training and orientation offered to local Indigenous hires. Yet, depending on how well people are prepared for industrial labor and urban Canadian cultural expectations, difficulties can arise. They may feel “out of place” in a white-dominated workforce, lose face as they learn through mistakes, or encounter misunderstandings with Euro-Canadians. Their lifestyles can be disrupted as they have less time to hunt or fish, and must rely on store food. Cultural heritage can become devalued or dismissed by outsiders, leading to hurt and confusion.

Negative social impacts such as alcoholism, family violence, and suicide can occur as a result of rapid cultural change. These impacts can be mitigated if cooperative planning between corporation and community takes place. Cross-Cultural Impact Assessment (CCIA) can be used to identify and help plan for these impacts.

A.1.b Corporate Objectives

Although the corporate motive is often thought of as profit, this is not the only corporate interest. Corporations are part of society and should be concerned not only with maintaining the “status quo” but also with the quality of life of people they contact. As the public becomes more informed of corporate powers and activities, corporations are increasingly expected to act in socially responsible ways. Petro-Canada’s environmental and social policies reflect this trend.

Differing perspectives exist, however, between corporations and communities. Energy corporations often focus on profit for shareholders, while communities emphasize human resources, quality of life, and self-reliance. Indigenous communities seek local control of development for autonomy and independence. These interests must be reconciled so that they coexist and ideally complement one another.

From the industry perspective, cooperation with Indigenous communities can be achieved for several reasons. According to Doug Bowie, Vice President for Environmental and Social Affairs at Petro-Canada (May 1981), corporate motivation for cooperation falls into four levels:

- Regulation – Cooperation is required by government regulation.

- Economic feasibility – Cooperation avoids risks and reduces expenses due to mistakes.

- Public opinion – Cooperation is necessary to satisfy public opinion.

- Social responsibility – Cooperation is desirable as a fulfillment of social responsibility.

The motivation for cooperation can strongly influence the success of CCIA. The higher the motivation, the more reliable and valid the results are likely to be. Often, however, the extent of cooperation depends on how much the corporation needs or wants from the Indigenous community rather than the projected impacts on the community. This tendency is reflected in the tools used in analysis.

Cost-benefit analysis, for instance, is often a tool for proponents only, offering only rough estimates of cultural impacts. CCIA should be designed for both the community and the proponent. Together they are better positioned to plan mitigation measures and direct development to create positive opportunities. Cost-benefit analysis can still be used to evaluate corporate outcomes but should not define the whole process.

Community-based impact assessment represents a stronger commitment to cooperation. It satisfies all four levels of motivation, provides opportunities for fuller appreciation of community perspectives, and helps maintain community autonomy, integrity, and cultural identity. For the corporation, it reduces risks, costs, and delays by ensuring impacts are identified and addressed early.

Community-based CCIA relies heavily on local voluntary and employed resources, encouraging extensive participation and fostering close cooperative relationships between proponent and community. This ensures that the maximum amount of local information is used, making the impact process more predictable and controllable. Community-based CCIA will be discussed further later in the report.

A.2 Indigenous Communities

Indigenous communities are quite different from each other in their traditional cultures, and in how they have changed through acculturation. Indigenous community development is one means being tried to help overcome impacts of industrialization.

A.2.a Diversity of Groups

Indigenous communities consist of a population of distinct people who share a common culture in a particular locality. They may be treaty First Nations peoples, non-treaty Indians, Inuit, Métis, or any combination. They may be distinguished by linguistic groupings such as Algonkian, Athapaskin, Sioux, or Iroquois; by ecological zones such as sub-arctic, arctic, boreal forest, plains, or coastal; or by other categories like treaty number, economic subsistence or extent of experience and ability in dealing with government and industry.

There is a wide variety of types of Indigenous communities. Unlike urban Canadian communities, Indigenous communities are generally relatively isolated. That is, they are not as socially and economically interdependent with external communities as urban communities are. They maintain their differences as a result.

A.2.b Traditional Group Similarities

However, despite their differences there are substantial similarities between Indigenous communities. Traditionally, most Indigenous groups were hunting and gathering bands or tribes. They could be described in the following terms:

- small groups: bands or camps

- fluid or unstable group organization (forming and dissolving), personalities more important

- high mobility; nomadism

- taking from the environment rather than replenishment of it; hunting, fishing, foraging

- little authoritarian leadership

- little specialization

- division of labour by sex and age

- egalitarian society (little social stratification)

- ideology of kinship, but not rigid

- little “ownership” of resources

- lack of strict territoriality

- feuding, but not large scale war

- polytheistic religion (many gods or spirits).

These characteristics were generally true but not always—exceptions were common.

Some Indigenous people were horticulturalists, namely the Iroquois. They could be characterized as having:

- investment in the environment; planting, tilling

- tendency toward stable groups; settled or semi-settled communities

- division of labour based primarily on sex and age

- basically, social equality; though social stratification may occur as reliance on cultivation increases

- pervasive ideology of kinship; kin groups become important

- development of notions of territoriality

- feuding on group level; wars may occur

- polytheistic religion, with or without a high god; ancestral veneration occurs.²

These classes of culture, hunting-gathering and horticulturism, are ideal types which likely describe no particular culture perfectly. Indigenous Canadians depended very much on the natural environment’s ability to produce food but their technologies enabled them to adapt to changing ecological conditions. Their culture evolved over perhaps 40,000 years of life on the North American continent.

Needless to say, modern Indigenous communities usually are no longer of hunting-gathering or horticulturalist cultures. Many pressures of acculturation have forced many of them into dependent economies struggling for any cultural identity.

A modern Indigenous culture tends to have these characteristics:

- larger, more stable settlement

- mixed economy: agriculture, trapping, hunting and fishing, wage labour, welfare, cottage industry

- increased social stratification and division of labour

- more formal education

- dependence on government for development of resources – increasing in autonomy

- more industrial technology

- more interdependence with other communities and more communication concerning outside issues

- monotheistic religion.

Indigenous communities adapt to pressures of urban Canada in differing ways and so the diversity among Indigenous cultures increases. These characteristics are still only partly true of any particular community. A culture is a very adaptive thing.

A.2.c Culture: Two Realities

Frank Vivelo defines culture as “the shared patterns of learned belief and behavior constituting the total lifeway of people; the totality of tools, acts, thoughts and institutions of any given human population.”³ By this definition it must be understood that culture consists of two realities: the physical (observable, objective, or empirical) reality, and the mental (experiential, subjective or psychological) reality. Though we do not know exactly how the two realities are connected, and some people believe there is only one reality, for the purposes of study we must treat them differently. Physical reality is directly observable (in common sense) and mental reality is not.

² Adapted from Frank Vivelo, Cultural Anthropology Handbook, pp. 53, 66, 1978.

³ Frank Vivelo, p. 242, 1978.

Though we can observe outward behavior of Indigenous people (or others) along with their technologies and essentially agree on what we see, we may differ greatly on how we interpret what is seen. We construct different mental representations of physical reality. The representations constructed by different people within a culture may be quite similar but representations constructed by people of different cultures could be very different. The culture one belongs to is very important in determining how one constructs his mental representation of physical reality.

A.2.d Subjective Culture

What another person sees in his reality is very difficult to determine at the best of times, but when a researcher from a petroleum corporation is trying to study the mental reality of an Indigenous culture, he must first construct a culturally biased representation of the observed behavior (the physical reality) of the Indigenous persons and then speculate on what this behavior means to them. In other words, there is no way to directly observe how anyone, especially of a different culture, makes sense of his world.

Some ways of describing the value and belief systems of Indigenous culture have been suggested by anthropologists. Traditionally, Indigenous people, living close to nature, maintained values and beliefs that were very essential for survival in their environment. They believed in harmony, not exploitation, in that destroying natural resources meant self-destruction. Many practiced calculated conservation. The ultimate test of truth of a belief was practice — a belief must be useful. This meant that truth was contextual — what works in one situation may or may not work in another. Beliefs must be adaptive as conditions change. Yet stability in the system was maintained by myths, folklore, and customs handed down orally from generation to generation. These concerned general do’s and don’ts (totems and taboos) that were required for survival and personal fulfillment.

Another aspect of subjective culture is the need for cultural identity and pride. Indigenous people, like all other groups or classes of people, need to feel good about their heritage. It is often expressed as ethnocentrism (cultural pride) or xenophobia — “we are the best” and fear of outsiders, respectively. A certain minimum amount of cultural identity and pride is required for cultural stability and development. Today, modern Indigenous people have had much of their cultural identity destroyed by urban Canadian attempts to assimilate them and make them economically and politically dependent.

As far as cognitive style or thinking style is concerned, Indigenous people have traditionally made extensive use of analogy — finding similarities among differences in experience. This is a pre-scientific style in which the use of inductive and abstract reasoning is underdeveloped. This is part of the cross-cultural communication problem.

Indigenous values are an issue of vital concern to modern communities. The National Indian Brotherhood has stated in a policy paper to the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development that Indian children should be learning that “happiness and satisfaction come from pride in one’s self, understanding one’s fellowmen, and, living in harmony with nature”:

- Pride encourages us to recognize and use our talents, as well as to master the skills needed to make a living;

- Understanding our fellowmen will enable us to meet other Canadians on an equal footing, respecting cultural differences while pooling resources for the common good;

- Living in harmony with nature will ensure preservation of the balance between man and his environment which is necessary for the future of our planet, as well as for fostering the climate in which Indian Wisdom has always flourished.

In brief the values here are:

- Self-reliance;

- Respect for personal freedom;

- Generosity;

- Respect for nature;

- Wisdom.

A.2.e Indigenous Community Development

Regardless of differences, all Indigenous Canadian communities are faced with threats to their lifestyle, their values, and beliefs.

In 1940 the Minister of the Interior, J.A. Crear, declared that the First Nations peoples were not “mentally and temperamentally equipped to compete successfully with the White population” and that therefore the government was abandoning its efforts “to equip the Indian to work and live in the white urban communities…”. The government-sponsored Hawthorn Report of 1967, which dealt in some detail with the conditions and problems of the First Nations peoples, stressed that: “…the general aim of the federal government’s present policy is based on the necessity of integrating First Nations peoples into Canadian society.” Indian leaders were suspicious of this approach, which they feared would mean “assimilation by coercion” rather than “participation by consent.”

The federal and provincial governments have, until the seventies, been making decisions for Indigenous people, without much consultation and without invitation to Indigenous communities to participate in administration.

One means of achieving control over their destiny is through Indigenous community development. This is locally initiated and regulated human and economic resource development. If a paternalistic attitude of the Federal Government has ensured that Indigenous people are kept dependent instead of self-reliant, being “kept” has stifled the learning of skills and the adapting of values and beliefs required for making a satisfactory living in the modern world. Many band councils and determined groups are now building their own schools, services and businesses. They adopt organizational styles and methods which are consistent with traditional styles and methods. They develop cooperatives, craft industries, adult education programs and social service centres. They have voluntary non-profit associations, and some are recovering almost lost or forgotten ceremonies and arts.

Some of this independence has been possible because of revenues from fossil fuel development, but much has been done by sheer will-power and self-education. These people are learning to use experts and consultants when necessary and to support local initiatives toward professional development. CCIA can be used by Indigenous people doing community development for planning and evaluation at the local level.

A.2.f Acculturation

The main continuous debate for Indigenous peoples seems to be how to maintain elements of traditional culture while adapting to new social, economic and political pressures and opportunities. When a fossil fuel resource development project impacts an Indigenous community, rapid acculturation can take place which can cause much confusion over cultural change. Acculturation may be defined as:

“cultural change that is initiated by the conjunction of two or more autonomous cultural systems. Its dynamics can be seen as the selective adaption of value systems, the processes of integration and differentiation, the generation of developmental sequences, and the operation of role determinants and personality factors.” ⁶

It is therefore very important that both the development proponent (i.e., Petro-Canada) and the Indigenous communities affected by the development projects be informed about possible cross-cultural impacts before these happen. The role of CCIA can be very essential in planning cultural development locally.

Perfect — here’s the final merged OCR text for Section A.3 (Standard Social Impact Assessment) with the last piece you just provided included:

A.3 Standard Social Impact Assessment (SIA)

Because of the special nature of impacts on Indigenous Communities by fossil fuel resource development projects, SIA should be reconsidered. “SIA’s often proceed on a common sense, ad hoc basis.” “To date, much … social impact assessment has been largely descriptive, unsystematic, and seldom comprehensively analytical.” These words, spoken by professionals in SIA, capture the current state-of-the-art in SIA. It is only a decade old and though it is based on the tradition of western social science it is a policy science and hence its fore-runners are only post World War II occurrences. SIA has been adapted and modified for a wide variety of situations, now including the cross-cultural setting.

A.3.a SIA for Whom and for What?

Generally speaking, SIA is a method used by developers, requested by governments, to determine how their development projects will affect the immediate human environments. The results of SIA are used by governments to determine what mitigation or compensation the proponent should be charged with if the project is to proceed. They are also used by the development proponent to determine whether the project is economically feasible, considering mitigation and compensation.

Another consequence of the SIA study, frequently only incidental, is to create community awareness of the proposed project. The awareness may or may not result in community action for or against the project.

SIA is usually done in a mono-cultural setting, or where both development proponent and affected community are assumed to be essentially of the same culture. However, a closer analysis of any situation will show that there are always cultural differences between social groups. These differences may be associated with geographic locality, economic class, ethnic origin, political status or ideology, education levels, or other shared personal attributes.

Canada has often been considered a cultural mosaic, a society of people or communities sharing some values and beliefs but not others. Whereas there are some similar cultural elements shared by all, there are differences which make each person and community different. When differences between Indigenous and urban-industrial Canadian communities are involved in a study and can be seen to include substantial cultural components, standard SIA must reflect the extent of those differences.

If SIA should always consider community impacts from the perspective of those impacted, more attention should be given to local perspectives when these are most different from the researcher’s perspective.

When impacts are clearly of a cross-cultural variety (energy resource development – Indigenous Community) the local perspective or understanding and evaluation of potential impacts must be given greater emphasis. The “objective” impacts to economy, demography, technology or infrastructure should be seen from the local perspective. This is because local people have to live with the changes or stop them in the ways they understand and value them in the context of their culture. The same applies to impacts to the subjective culture.

On a continuum then, CCIA is SIA which is designed to emphasize the study of impacts of acculturation where cultural differences between proponent and community involved are relatively large:

Standard SIA ————————————————————— CCIA

Cultural Homogeneity —————————— Cultural Heterogeneity

A.3.b Actors and Their Roles in SIA

The developers are the initiators of the SIA process as they want to develop a resource such as oil, gas or coal (or highways, high-rises, parkland, power dams, etc.). They are responsible for conducting the SIA. They are responsible for ensuring a minimum of disruptions to local human environments which require mitigation or compensation for imposed changes.

The governments involved represent the public interest in general. They set regulations, guidelines and criteria for evaluation of SIA results. Governments may have unofficial objectives as well, such as development itself or use of SIA information for other purposes.

The communities who are to be affected by development participate in SIA via public participation programs. Ideally, they are given the opportunity to become informed about the project and to give their ideas and opinions to the proponent and government officials. Public participation is seldom popular among community residents unless the project is potentially highly dangerous to their way of life. Residents are frequently suspicious of SIA community liaison officers and doubtful that they really care about the community. Residents should be encouraged to participate by demonstrating the potential rewards to be experienced. Public participation is practically essential in SIA if valuable information is to be recovered.

A.3.c The Process…Briefly

The SIA process starts with review of literature about the community (local newspapers, government statistics, historical records, etc.) and some preliminary discussions with residents. Issues of concern to the community are identified and serve as the basis of SIA focus. Data collection usually consists of taking an inventory of socio-economic data (population, incomes, buildings, services, etc.) that can most easily be quantified. Indicators are used as “measuring sticks” of various directly unmeasurable variables such as social cohesion, religious commitment or mental health. The profiling of the community involves integrating the data to get a clearer picture of the state of the community.

From this profile two projections are made about the future development of the community. One scenario depicts the future of the community with the development project; the other, the future without the project. This is to determine the extent of change due to the project itself.

The likely significant consequences of going ahead or stopping the project are then assessed. Sometimes an evaluative stage is also completed but this may be considered the responsibility of government and corporate decision-makers.

SIA has depended largely on quantitative analysis and cost-benefit analysis as final decision-makers like the simplicity of numbers and dollars. However, much of SIA does require the use of such techniques as social surveys, interviews and public meetings, all of which imply a heavy qualitative component. The expression of values, beliefs, opinions and attitudes can only be quantified after suitable categories have been applied in their analysis.

As was mentioned earlier, SIA is in an early stage of development. Many methods have been applied and different theories have been used in constructing methodologies. SIA has been guided quite a bit by practice, considering the individual circumstances differing with each project. Differences also occur as the researchers’ expertise and professional backgrounds differ.

The use of the SIA scheme in designing CCIA content and process should be studied in relation to the cross-cultural setting.

Got it. Here’s the clean OCR + merged draft for A.4 (from the start through subsections a, b, c, and d up to this latest page):

A.4 Inadequacy of SIA Content

SIA is different from CCIA in the focus of the subject matter studied. The differences may be discussed in terms of objectives, quantitative–qualitative distinctions, disciplinary conceptual framework, causation, and the subjective–objective orientation. The objective is to find the necessary modifications of SIA as extensive cultural change is possible.

A.4.a Cultural Differences

The main objective of SIA is to assess impacts on observable social variables assuming little substantial change to subjective culture. When the impactor and impactee are of very similar cultures this objective may be satisfactory. However, when fossil fuel resource development projects impact Indigenous communities a cross-cultural impact situation results and different emphasis needs to be given.

Traditional Indigenous and Euro-Canadians do not interpret their realities in the same way. Changes to or impacts on Indigenous communities must be understood in the same way the local residents understand them. Special efforts need to be made so that sharing information and perspectives leads to the fullest understanding between the two groups about the nature of potential cultural change.

More specifically, this means that CCIA must include an extensive analysis of values, beliefs, attitudes, identities, folklore and thinking styles of the Indigenous people to be impacted. These aspects of culture are systematically related to each of the objective cultural aspects, such as technology, social behavior, social organization, and so on.

The local value and belief system must be studied rigorously to determine how it will control and regulate changes throughout the whole culture. In addition to calculating or researching local incomes, for example, as SIAs usually stress, more attention must be given to how local Indigenous people view their incomes. School attendance records must be interpreted in light of local social and economic opportunities, values and beliefs. Often SIAs will determine the number of certified tradesmen in the local job market. CCIA should be capable of showing how many residents actually have practical skills and abilities or potential and desire for employment.

A standard SIA might project an increased demand for social services in an impact area. In a cross-cultural setting a CCIA could be used to project a need for a particular type of service designed for the local culture. This could also mean recommending “preventive” labour practices such as appropriate time off, work and cultural orientation, or hiring family groups as work teams, in addition to “curative” measures like counselling, treatment for alcohol abuse or pay raises.

A.4.b Quantitative – Qualitative Differences

Because of greater emphasis on subjective culture and its direct observation may be impossible, methods used will be primarily qualitative, not quantitative, in CCIA. Values and beliefs, for example, are very difficult to quantify. Values may be prioritized and beliefs may be categorized, but at this time no measurement instruments are available for those that are unobservable.

The causal and logical patterns between beliefs and between values can be traced with difficulty, but this art will improve with practice and computer use. Eventually, quantitative data on subjective culture may be possible.

A.4.c Non-Disciplinary Conceptual Framework

SIA has usually depended on either disciplinary, multi- or cross-disciplinary, or interdisciplinary conceptual frameworks for the analysis of its subject matter. But these frameworks cannot fully represent Indigenous culture.

Indigenous culture, like Indigenous thought, is conceptually broken down in different ways than urban Canadian culture. Western social scientific thought is generally adapted to Western society. It is divided into disciplines of history, sociology, psychology, economics, political science, human geography and anthropology. Of these, only anthropology can be considered fully interdisciplinary, as it studies the whole socio-cultural system, but even anthropology imposes on its subject a set of concepts that make sense mainly for Western social scientists.

Indigenous culture requires more than these concepts as Indigenous people see their culture in different terms. Multidisciplinary or cross-disciplinary analysis lacks the integration of information that is needed to accurately represent the actual integration that occurs among parts and events within a culture. Even a fully interdisciplinary analysis cannot capture the “holism” that is present in an actual culture.

The “holism” of a non-disciplinary analysis implies that no set special causal relationships are to be considered isolated. The economy, social organization, cultural psychology, politics and technology of a community must be seen as a whole system, not as isolated systems studied separately and then theoretically integrated.

Only a non-disciplinary conceptual framework can incorporate the ideas about their cultures that Indigenous people have. A non-disciplinary analysis can be designed by CCIA researchers and concerned Indigenous people as required to meet both sets of standards. The outline of such a framework is offered later in this report.

A.4.d Patterns of Causation

Working within a non-disciplinary conceptual framework, a researcher must be prepared to analyze any causal relationship within a community or culture. Several patterns of causal relationships have been determined: uni-linear, multi-linear, non-linear, mutual and cyclical. SIA generally has depended on the social science models of causation which are usually based on linear, multi-linear and non-linear patterns.

Uni-linear causation is simple: A causes B in a constant relationship or at a constant rate, regardless of conditions. This view is usually highly abstracted from empirical observations and is unrealistic. It helps researchers simplify complex situations by deleting information.

Multi-linear causation is also fairly straightforward: A and B and C together cause D, in a constant relationship or at a constant rate, regardless of time and place. It too is an abstraction for simplification.

In the case of non-linear causation the relationship or rate of causation varies depending on conditions of time and place. Multi-factor and single-pair-factor relationships can be non-linear.

In mutual causal relationships A causes B which simultaneously causes A. Things cause each other to change or to continue. This view of causation is most realistic when combined with multi-factoral causation and thought of in terms of time. The result is cyclical causation:

ABC→A¹B¹C¹ → A²B²C², … AⁿBⁿCⁿ; or ABC⇄DEF; or DEF⇄ABC.

This is the analytical tool needed for understanding culture. When it is used to interpret relationships in a whole community the set of relationships between factors or variables constitutes a systemic or network pattern of causes.

Examples of Causal Relations

| # Type | Example | |

| 1. Uni-linear | An increase in family income causes a proportional increase in household technology. | |

| 2. Multi-linear | Decreases in illiteracy, unemployment and child abuse together cause proportional decreases in crime rates. | |

| 3. Non-linear | At first, new residents are novelties, but later, further new residents are commonplace. (statement of person-perception change) | |

| 4. Mutual | The way in which George speaks influences the way Mike listens, and how Mike listens affects the way George speaks. | |

| 5. Cyclical (Mutually Reinforcing or Counteracting) | Each time a citizen’s group goes to city council they are met with greater objections to their proposals. Because of this the group demands more in their proposals. The conflict escalates, each group blaming the other. | |

| 6. Systemic | Available housing depends on incomes which depend on employment which depends on education which depends on parental values which depend on social status which depends on housing. Each is influenced by all of the others simultaneously. |

These examples illustrate various forms of, and perspectives on causal relations. The most realistic pattern is the one which makes most use of available information, the systemic pattern. It includes each of the other patterns as subsystem components. In the study of Indigenous communities it must be possible to synthesize these subsystem components or to isolate them depending on the purpose of analysis. A subsystem component such as the impact of employment on the values of Indigenous people toward their families can be seen as a unilinear (single pair) relationship, for simplicity, or as part of the systemic pattern for realism.

Summarizing the content of CCIA, a non-disciplinary systemic analysis of the Indigenous perspective of cultural impacts is required. The subjective reality of Indigenous people differs from that of urban Canadians, is not directly observable, is presently unquantifiable and is the seat of control of the physical culture. It is necessary to find out how the subjective experiences (values, beliefs, identity, thinking) may be impacted and how they will regulate observable changes.

A.5 Inappropriateness of SIA Process

There are several problems in trying to apply the SIA process to the cross-cultural situation just as there are in applying its content. Special attention must be given to

- cross-cultural communication

- the extensive interpretation of subjective experiences through conversation and observation of behavior

- the problem of rapid acculturation and uncertainty; and finally,

- the diversity among Indigenous groups.

A.5.a Cross-Cultural Communication

In conducting CCIA the community liaison, public participation, and participatory research component processes involve extensive cross-cultural communication. Whether researchers are Indigenous or White, information gathered on site must eventually be translated into the language of policy decision makers. Two symbolic universes come into contact and barriers are formed where concepts in one language do not have equivalents in the other. Two-way learning of these different concepts must take place if the two cultures are to communicate. Body language, gestures, expressions and differing uses of language must be understood as well, as they convey meanings that words cannot.

The very significance of having a meeting cannot be assumed as it might be in a mono-cultural setting. The use of questionnaires, interviews and public meetings cannot be adopted from mono-cultural SIA processes. Arranging times, places, specific issues to be addressed and appropriate behavior mean different things in the two cultures. Changes must be made in these methods.

Bias, either intentional or unintentional, should be avoided at all costs, although it may never be eliminated. Self-analysis, or introspection should be considered whenever there is any doubt about bias and objectivity – ask yourself to be honest and thorough.

A.5.b Analysis of Subjective Reality

As the main subject matter is subjective, that is, how the local Indigenous people think about their everyday experiences, special methods of analysis must be used. There are methods (ethnomethodology, for instance) which are designed for this purpose. Usually, these consist of getting to know the local people on an equal basis, living like they do and empathizing with them. This process takes quite a long period of close interaction with the people but skilled researchers can learn to observe and interpret observations quickly. As this method is developing a history certain rules or principles of observation and interpretation are becoming common. It is learned that certain similarities and differences occur between cultures and these become expectations that speed analysis.

Another indispensable method that is gaining repute is participatory or community-based research. This means not only public participation but, among other things, hiring local qualified or trainable residents for designing and doing the research. These indigenous researchers are given considerable freedom, guidance and resources to report on how local people perceive and value their community and culture. It is sometimes felt that as insiders they have less bias and fewer misconceptions about local concerns. However, these researchers may be biased in favour of local sentiments, they may be partisan to particular insider groups and they may have difficulty translating the local Indigenous culture into urban Canadian language. These problems could be partly overcome by having both insiders and outsiders on the research team.

SIA methods of social surveys and statistical analysis cannot penetrate into subjective reality of peoples of a different culture. Even the use of social indicators has to be greatly modified for CCIA. Social indicators, such as suicide rates, divorce rates, participation in voluntary associations, all could have different meanings in Indigenous communities. How these rates are to be interpreted brings us back to subjective analysis.

A.5.c Rapid Acculturation

Rapid acculturation (cultural interaction and change) can happen when a fossil fuel resource development project locates near an Indigenous community. This creates much confusion and uncertainty for both groups involved. The uncertainty leads to speculation, rumors, gossip and incorrect information. In a state of confusion anything can happen, there is little predictability. It is therefore necessary to have continuous contact, communication and input to the CCIA process. In a mono-cultural SIA study, the subjective cultural variables are considered relatively constant in analysis, assumed to change very little. If there is in fact little change, prediction can be fairly reliable. But in CCIA, information used in simulating the community must be updated more frequently and completely as changes take place. Cross-cultural changes can have very pervasive impacts. Cultural changes may be fast and temporary or slow and permanent. They may be reversed, as in “trial-and-error” development, or cumulative, as in multiplier or exponential growth development. Changes in the way people view their world can be more devastating than changes in community infrastructure or technology, because values and beliefs are the controls at the community level.

Intensive community research and planning may be required in preparation and regulation of cultural development. Again this means close interaction and cooperation between proponent and community.

A.5.d Diversity of Indigenous Communities

The diversity of Indigenous groups in Canada leads to the need for flexibility in CCIA process methodology. Indigenous cultures vary in ways that urban Canadian culture does not. Although SIA includes some very versatile tools most SIA researchers are not prepared for differences in say, communication styles of Inuit, Metis and Dene. CCIA researchers must be prepared to design processes to simulate northern communities with 90% unemployment rates, traditional hunting-gathering bands or modern industrialized near-urban communities. Without such adaptability the CCIA process could bias or falsify information from communities.

A.6 SUMMARY OF THE CCIA PROBLEM

In order to answer the questions raised at the beginning of this section a CCIA researcher must consider several issues:

- the nature of the development project:

- serving the interests of shareholders and the energy needs of the economy

- instigating CCIA for self (proponent), government and community needs

- policy regarding protection of natural and human environments

- the points of contact between project and community

- approach taken in cooperation with community

- meeting government regulations.

- the nature of the community:

- demographic and ethnic composition and history

- how points of contact with project are impacted respond and adapt

- how community can use CCIA as a planning tool

- how proponent is viewed – cooperation, suspicion, avoidance

- level of community competency in dealing with industry and government

- components of cultural system potentially impacted

- state of knowledge in cultural anthropology

- community’s values, goals and aspirations.

- the nature of SIA and CCIA:

- the subject matter of impaction – objective or subjective reality

- type of information – qualitative or quantitative

- the end use of information by proponent, governments and community

- relationships between proponent, government and community – cooperation, avoidance, confusion

- steps, stages, phases in CCIA process

- theory, approach, strategy, methodology, methods and techniques available for employment and their actual use

- way in which all considerations are related and integrated

- time, money, resources available.

In short, these are the problems involved in doing CCIA. The final statement produced in a CCIA says what will likely happen to the Indigenous community and its culture as a result of the fossil fuel resource development project. If it is designed for use by proponent and community it can be used as a tool in planning community and cultural development. The proponent can use it to reduce risks and uncertainty and so minimize costs and delays.

Although it is evident that the development proponent is impacted as well, in its interaction with Indigenous communities, the subject is beyond the resources at hand for the present report. However, it should be kept in mind that the corporate organization is in many ways similar to a community and that it functions within its own sub-culture of urban Canadian society. A cross-cultural corporate impact assessment might look similar to the CCIA developed in this report.

Now that the problems of CCIA have been identified a theoretical framework must be developed from which a detailed CCIA methodology can be designed.

B. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF CCIA METHODOLOGY

In light of the problem of CCIA as defined in the first section the methods proposed for achieving a final CCIA statement will require rationale and justification. The study of methods and their use constitutes a methodology and this consists of a set of theoretical concepts and assumptions. Because no single theory seems adequate or wholly appropriate for making sense of CCIA methods, concepts from various theoretical perspectives need to be synthesized or welded together for that purpose. The result is to be a “holistic” or non-disciplinary theoretical framework.

This framework will draw from: 1. theory of science and knowledge processes; 2. theory of systemic causation; 3. theory of subjective reality construction; 4. theory of cultural perspective paradigms; and 5. ideas on the nature and study of impaction. Combining these sets of ideas creates the basis not only for the interpretation of methods but for their invention and/or adaptation.

Perhaps ideally, for the study of Indigenous communities and cultures there should be an Indigenous science. Such an anthropology built by Indigenous people and based on Indigenous cognitive styles or thought, if it is ever to be realized, will be a long way off in the future. This report may however, encourage that enterprise.

One central set of concepts ties together the theoretical framework. Essentially, both the science of CCIA research and the community being studied consist of information processes. Homo sapiens is a conscious information processing biological organism. He exists because he keeps a mental map of his surroundings complete with charted dangers and attractions. The mental map or representation guides human behavior toward survival and the achievement of happiness.

Researchers doing CCIA in an Indigenous community must somehow represent the community and its culture so that the development proponent can act out development plans and fulfill its goals without destroying those of the community. Science provides a system of procedures to follow to help create that representation. Scientific reasoning, however, is not different from the logical-empirical reasoning of common sense, it is simply more consistent, coherent and systematic. All processes, rules, criteria and products of scientific information processing are basic to human thinking, but they have been refined to greater efficiency and effectiveness. Whether a scientific truth is better than a common sense truth is a matter of personal judgement and often depends on applications.

The empirical content of the social sciences has evolved over the past century. The theories, hypotheses and concepts help in the interpretation of a socio-cultural system. They are tentative, not final truths. They may be true in one situation but not in another. Yet, they form the framework of interpretation of social phenomena and give it special meaning. CCIA researchers apply their knowledge and get a perspective on the Indigenous community and culture studied. They are information processors.

The Indigenous community also functions as an information processor, with all its processes, rules, criteria and products that help its residents make sense of the world. It is these processing components which determine how the Indigenous community as a whole and as individual residents will respond to impacts from fossil fuel resource development. The information processing procedures and mechanisms need to be studied.

The impact situation is viewed differently from proponent and community. Each group has evolved its own way of representing reality. How the two interact and affect each other must be understood. Therefore, the proponent’s information processing procedures and mechanisms must be understood as well.

The only way to understand the local Indigenous perspective is to have the local people participate in the design of the research. This will help ensure that the right categories of thought and value are used and that communication is complete and without urban Canadian bias.

In the chapters that follow, the case for this outlook on research and community is argued for more clearly and thoroughly.

The task of designing a CCIA research methodology is accomplished by viewing the summary of the CCIA problem through the theoretical framework that follows.

B.1 Theory Of Science And Knowledge Processes

Science as a process consists of a series of steps that deal with the understanding of experiences. Two primary activities in the process are empirical research and theory construction. In CCIA researchers are interested in how to get relevant information about an Indigenous community’s culture (empirical research) and how to make sense of that information (theory construction). Thus the methodology of CCIA must be designed for these two activities. An overview of some important parts of scientific processes and their roles in knowledge follows.

B.1.a Steps of Scientific Thought

Historically, science is a product of Western civilization with roots in ancient Greek philosophy. It has evolved through centuries of practice, trial and error and speculation. One central set of ideas that has become clear and distinct in the scientific process concerns the use of logical deduction and induction. Although there is much controversy surrounding issues of induction, the logic of scientific reasoning can be expressed in the following way:

- empirical observation of objective reality (perception);

- description of observations (conceptualization);

- identification of causal relations (explanation);

- construction of general explanation of observed and unobserved objects and events (induction);

- construction of hypotheses or predictions about yet unobserved objects or events (deduction);

- empirical observation anticipating (or not anticipating) predicted objects or events; return to step one.

This sequence of steps in the logic of science is cyclical so it is misleading to start or stop at any particular step. Another way of expressing these pertains to the objectives of science – to describe, explain, predict and control phenomena (objects and events as experienced). In CCIA the researchers will be using these various levels of thinking in order to analyze and plan for cultural impacts.

B.1.b Levels of Knowledge

It will also be useful to understand more particularly, the various levels of scientific knowledge into which the various ideas in CCIA may be sorted. These levels can be broken down into:

- paradigms

- theories

- models

- simulations

- empirical data

Briefly these can be interpreted to mean the following things:

Paradigm (Para-dime): a system of thought characteristic of or common to a group or population of people; utilizing a core set of ideas that creates coherence and orientation for the whole system; perspective used to interpret a science, religion, philosophy or political-economic ideology, etc.; the broadest sense in which values, beliefs or ideas are related. Examples: scientific perspective of empiricism or logical positivism; religious perspective of polytheism.

Theory: an integrated set of concepts construed to represent or potentially explain a general kind of experience (phenomenon) usually in causal terms; considered to be potentially valid for both observed and unobserved phenomena of the same type. Examples: scientific theory of atomic structures; common sense theory of: people who are similar are attracted to each other.

Model: a type of theory that uses physical structures or two dimensional figures (diagrams or pictures) to represent a phenomenon; in some way functions or operates like the real system that is represented. Examples: scientific model of atomic substructures (rods and spheres representing particles and bonds); common sense model airplane, or map of geography (may or may not be used as an explanatory device); human anatomy used to explain social organization: brain = government, legs = transportation modes, circulatory system = economy, etc.

Simulation: a type of model that includes proportional representation; acts like the real thing through time; may employ exact empirical data about the real system; used to make predictions, forecasts or projections concerning changes in the real system as component variables may be manipulated quantitatively. Examples: scientific simulation of aircraft flight using scaled down planes in wind tunnel; psychology experiments with “Prisoners Dilemma” – laboratory controlled human cooperative behavior.

Empirical Data: minimally interpreted information gained by observation of publicly observable phenomena; about some system believed to be real, not imaginary; can be biased by perception as perception involves selection and organization of data; must be interpreted conceptually and possibly theoretically before being understood; can be classified as nominal, ordinal, interval or ratio levels of qualitative – quantitative measurement. Examples: social science statistics on incomes and observed mob behaviour; heights and weights of children; verbal expression of values held.

It is not known to what extent these levels of information, belief or knowledge are universally human and how much is culturally determined. Thoughts and thought processes might be understood differently by Indigenous people (or others) and they may in fact operate differently. There may be substantial differences in cognitive style (patterns and modes of thinking).

B.1.c Examples of Use

It is helpful to know the level of analysis reflected in certain beliefs about Indigenous cultures. Whether the researcher chooses to use a Western social scientific paradigm or develop an Indigenous analytical paradigm, for example, is an important decision considering the relative amounts of structured information contained in each. The value of theories that were previously simply assumed by a researcher may be put in doubt by empirical data. It is important to be able to select the appropriate data from observations for the construction of simulations so that good predictions can be made.

Scientific reasoning can be used to get from one level of knowledge to another. By using more abstract and general reasoning in induction knowledge becomes more simplistic and loses its concreteness or realism. Thus in understanding the most abstract ideas in the Indigenous culture a paradigm is constructed that runs parallel to the paradigm used by the researcher. When this level of analysis is used by the researcher he may become less sure of the validity of his interpretation. Then hypotheses should be deduced from theories about the Indigenous cultural paradigm so that the ideas about the paradigm can be tested in predicted empirical observations. Scaling up and down the levels of knowledge is a continuous process as higher level knowledge is always being adjusted to explain, predict and control empirical observations.

B.2 THEORY OF SYSTEMIC CAUSATION

Another key concept in scientific thinking is that of causation. Science attempts to understand events in terms of causal relationships. It was mentioned earlier that the systemic causal network pattern of explanation could serve in the analysis of cultures. If this view is taken, as it is in this report, then it is possible to look at a culture or a cross-cultural impact situation as a whole system. The systemic causation paradigm of science can be used to create theories about an Indigenous community’s culture, model its subsystem components, simulate its development and predict or project future impacts.

B.2.a Real and Conceptual Cultural Subsystems

In the systems view of a community all subsystems, real and conceptual, are causally interdependent. The “real” subsystems such as families, institutions, organizations, individuals and so on, rely on each other for the satisfaction of their material and mental or psychological needs. Conceptual subsystems, which depend on cultural cognitive styles, could be divided into the subject matters of the various social sciences – economy, politics, social organization and psychological systems. Non-disciplinary systemic means of distinguishing conceptual subsystems may be exemplified by cybernetic (science of control and communication)

terminology: control, regulator, environment transformer, target effect, feedback and information flows and energy flows. These cybernetic subsystems are interdependent on a basis of structural – functional logistics. That is, they depend on each other logically to explain the structures and

their functions in a community (see Figure 1):

Transformer: Social organization, behavior, exchange, technology;

Target Effect: Community needs (i.e. food, shelter, association, etc.);

Regulator: Decision making, problem-solving, planning, evaluation;

Control: Traditional values, beliefs, customs, etc.

Environment: Social, physical, biological.

Other system science views of a community and its culture have been designed as well. One that simplifies the community greatly conceives the community as consisting of three basic components: input or detector (sensing, thinking, knowing), throughput or selector (valuing, wanting, choosing), and output or effector (acting, doing, behaving). Each real subsystem of a community, a family for instance, has structures to function for detection of problem situations, selection of problem solutions, and effecting or carrying out problem solutions (see Figure 2).

Another systems view of community focuses on the dynamics of variable interaction. This model of system dynamics makes possible computer simulations of community by using quantitative values for variables and mathematical equations for relationships between variables. This model uses the feedback loop concept extensively (see Figure 3).

B.2.b What is a System?

In essence, a system is a network of subsystems and patterned relationships between subsystems which form a whole that is relatively independent of systems beyond its boundaries. The subsystems remain in these relationships as long as their needs are met or until they are displaced by other forces or processes. Change can take place initiated by internal development or evolution or by impacts from external or environmental systems. For example, a traditional Indigenous community consisting of a number of families living together may stay together as long as there is enough food in the area to support them or until there is disagreement among them concerning sharing of responsibilities or resources. Thus, a theory on the determinants of social cohesion may be constructed.

It is generally believed that systems strive for a balance or equilibrium of flows of energy and information between subsystems. In a community this could mean that there is sharing of food so that all are equally well fed. But depending on local values, this may mean that each is fed in proportion to his contribution to the common good. Either way the equilibrium concept applies, only local priority systems differ.

Systems also strive for some degree of growth, or development. This could be represented in attempts to find a better way of building shelters, or a better way of generating local employment. It is not simply “improvement” but some qualitative change in means used to satisfy needs or solve problems.

The mechanism that makes the achieving and maintaining of equilibrium and growth possible is the feedback loop. Feedback loops consist of exchanges of information (or materials) between subsystems. Negative feedback information in the form of a hungry baby’s cry causes a parent or older sibling to provide the needed food. Knowledge about the local supply of food serves as feedback which causes food providers to get the food. In the same way, if an Indigenous group feels that its demands for more information from a developer are not being heeded it can provide the developer with feedback (letters, protests, public statements) to encourage compliance.

Positive feedback is used in reinforcing growth and development. When a new idea is acted on to solve a problem its success encourages further use of the idea. For example, if an Indigenous person tries wage labour for the first time and likes it he may encourage other members of his family or community to try it. Of course, if he does not like it this will constitute negative feedback as he will discourage others from trying it.

Literally, thousands of examples of feedback can be given because all communication is used to indicate to others that needs are or are not being met adequately. Once a message is communicated the receiver decides how to respond (supply for requests, deny requests, etc.) and acts on that decision.

B.2.c The “Holistic” Community System

It is at this point that we realize the “holistic” nature of the community system. Communications can take place, along with exchanges of material goods and services, between any number or combination of community real subsystems. Each subsystem must decide, on the basis of its value and belief criteria, what other subsystems to interact with.

On the basis of communications and a description of a job to be done (and other unspecified criteria) an employer hires one of many job applicants. One can imagine the number of possible alternative considerations the employer could evaluate for each applicant. Above all, his decisions may be irrational, partly rational or highly rational. Thus, in this single social phenomenon of hiring, there is high uncertainty as to the outcome.

A community made up of hundreds of these decisions everyday could never be fully simulated. The task of minimizing the uncertainty and reducing the variety of possible outcomes in a given situation requires that the researcher determine as many key operating factors as possible and discover their main relationships.

Just as one can get to know an employer and can guess fairly accurately which of the job applicants is most likely to be chosen, it is possible for a CCIA researcher to get to know an Indigenous community and its people and estimate how they will respond to certain defined impacts. Acquaintance ensures not certainty but a greater probability of development projections.

If CCIA researchers use the systemic causation perspective it is possible to account for many or most of the important variables operating in an Indigenous community. Models and simulations of systemic causation in Indigenous communities can be constructed and used to systematically project cross-cultural impacts. They can be used by local residents to plan their community’s cultural development on an ongoing basis.

One aspect of vital importance in an Indigenous community’s culture is the subjective reality and its components of values, beliefs, identity and cognitive style. These form the main control mechanism of any culture nd can be explained in systems concepts. How Indigenous people think, what they believe and what they value determine how they act in any problem-solving situation. Their identity and pride motivate the use of culturally prescribed behavior and problem solutions.

B.3 THEORY OF SUBJECTIVE REALITY CONSTRUCTION

If the theory of science and knowledge processes provide a logic for CCIA methodology, and the theory of systemic causation provides the structure of the subject to be studied (systemic causation) then the theory of subjective reality construction provides the humanistic perspective to the subject studied. In other words, a framework for the study and methods of CCIA must include insight into and empathy for the “humanness” of culture and community. Along with a set of theories as to how to study the human and subjective character of Indigenous communities, this section can facilitate, inspire and encourage CCIA researchers to acquire a sense of empathy for the people to be studied. Remember that how Indigenous communities view impinging fossil fuel resource development projects and how this perspective is impacted is the primary subject of study.

B.3.a Perspective

The key term in reality construction is “perspective”. By this it is meant that knowledge is contextual or dependent on: 1. the biology of the human brain; 2. personal learning experiences; and 3. the system of shared values and beliefs in the culture of a community. Each person in each community in each culture has a different perspective on the nature of things. At different times in a person’s life or in community’s (or culture’s) development different perspectives are used or held. “A perspective is an ordered view of one’s world – what is taken for granted about the attributes of various objects, events, and human nature… it constitutes the matrix [conceptual structure] through which one perceives his environment”.⁹

A perspective allows us to see a dynamic changing world as relatively stable, orderly and predictable. It serves as the basis of our actions and it can be changed depending on the successes of our actions:

The human being identifies with a number

of social worlds [people], learns through

communication the perspectives of these

social worlds, and uses these perspectives

to define or interpret situations that are

encountered. Individuals also perceive the

effects of their actions, reflect on the

usefulness of their perspectives, and adjust

them in the ongoing situation.¹⁰

⁹ Tamotsu Shibutani, 1955:564, in Joel Charon, Symbolic Interactionism, 1979.

¹⁰ Joel M. Charon, Symbolic Interactionism, 1979.

B.3.b Study of Subjective Reality Construction

Subjective reality construction concerns the processes involved in making sense of everyday experiences. The problems associated with this issue can be expressed in the following questions:

1. What is the nature, essence and meaning of experiences such as sense-perceptions, thoughts and emotions? (philosophy studied in phenomenology and epistemology).

2. What is the role of knowledge in a community in relation to social organization and social behavior? (studied in sociology of knowledge)

3. What are the objective characteristics and processes of a community’s belief system? (studied in sociology of belief)