Abstract

“Community Systems Science: A Paradigm For Development” introduces a framework for applying general systems science to human communities, divided into three main parts: Theory, Analysis, and Synthesis. Part One explores the essence of community and its evolution, presenting the idea of communities as self-sustaining systems rooted in human nature and survival instincts. Part Two dissects community structure and function, comparing communities across an evolutionary continuum and highlighting elements like networks and development processes. Part Three illustrates how communities can be designed and managed using system principles, with examples such as space colony design and cross-cultural development. While successful in its aim, the document acknowledges potential alternative approaches and unresolved issues in community systems science.

- Abstract

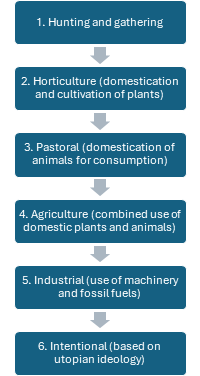

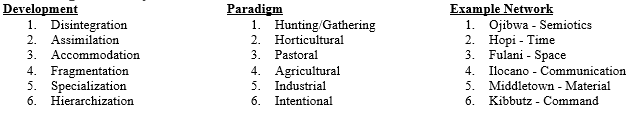

- 1.1 Community Universals

- 1.2 Community Evolution

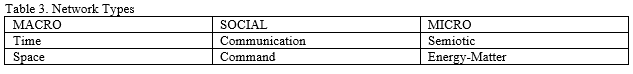

- 2.1 Community Networks

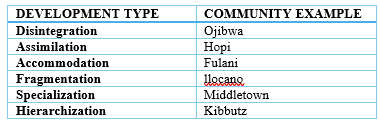

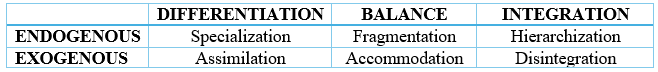

- 2.2 Community Development

- 3.1 Community Systems Engineering

- 3.2 Community Systems Management

- 3.3 Conclusion

Preface

Community Systems Science: A Paradigm For Development was undertaken as a result of the author’s felt need to understand and to help others understand the complete human community. This task has involved four major objectives. The first set of objectives, and most general, are taken from the group of objectives often attributed to science in general: to identify, describe, explain, predict, and control community. The second is to integrate the perspectives of the traditional social sciences – history, human geography, economics, political science, sociology, social psychology and anthropology.

The third objective is to provide a means by which one can view community as a whole, not merely as a sum of parts. The last objective is to be able to represent and control the processes of dynamic change in community behavior. Each of these objectives, if achieved, would allow one to understand the complete community in some way.

The rationale for choosing the particular divisions found here among parts and chapters is the author’s- belief that human reason functions to produce a theory or model of reality through the processes of taking things apart and putting them together (analysis and synthesis). Also, it was felt that there are basically two ways of viewing anything: cross-sectional and longitudinal perspectives. That is, in terms of a cross-section of organization and a longitudinal record of change. The result, of course, is theory, analysis, and synthesis viewed in terms of organization and change.

The development orientation for this scientific paradigm was chosen because the only real reason to understand anything is to finally be able to control phenomena for one’s advantage. Understanding community may be interesting in itself, but without leading to community development control such understanding is left wanting. An effort was made to make the examples of communities used representative of the wide spectrum of known varieties. This was done to reinforce the claim that communities have universal similarities and that development principles can be applied anywhere at any time.

Much literature research and creative critical thinking was done in the preparation of this work. Because it covers so many topics the thesis could not be fairly expected to deal with each topic as well as some readers would desire. The main task was to bring together in a coherent fashion information from many different disciplines and case studies. Many of the ideas researched are on the cutting edge of science. They may be controversial or disputable, but they are usually very thought-provoking. After well over a century of analytical positivism in science it is time to bring old ideas together with the help of new ones.

Systems science is one relatively new way of -integrating diverse sciences and enabling holistic perspectives. But because it dares to challenge and alter the scientific status quo it is open to many criticisms for not complying with established criteria in scientific methodology. For one thing, in emphasizing integration, process, and synthesis, systems science tends to demand extensive creative induction. It cannot, by its very nature, always comply with the demand for deductive logical certainty. Scientists must begin to realize that endless reduction of reality into its atoms leads to a body of knowledge and people who are isolated from one another. In their isolation, by specialization, members of a scientific community become disintegrated, and the community becomes a mere fluid sum of parts. Knowledge must grow by integration as well as differentiation if it is to represent reality. The relations between entities must be studied as well as the entities themselves.

It may fairly be said that the role of science is to reduce uncertainty and irrationality; science never succeeds in eliminating either of these. Knowledge will always be finite while ignorance eternally infinite. Man’s ignorance begins in his essence, the irrational and unknowable value-laden foundations of thought. To introspect is to proceed in a seemingly infinite regression of more subtle assumptions, yet one must accept some initial assumptions if one is to get anywhere. Once thought is in action ideas can be selected on the basis of their fruitfulness. The ideas composing the main body of systems science seem to this author to offer the best currently available set of operational assumptions for scientific reasoning. The fruitfulness of these systems ideas is to be demonstrated in this thesis. These ideas do not replace or try to influence value judgements in any predetermined way, they are instruments that help make value judgements easier and more successful in determining the user’s desired outcomes.

Many different approaches and applications of system science are now available. They are not all consistent with one another on all issues. Control, communication, information and game theories, cybernetics, artificial intelligence, and operations research are some of the special areas within systems science. Applications to social science by Talcott Parsons, Walter Buckley, Alfred Kuhn, and others are all very different from each other, even though the same central concepts and principles are used. There seems to be little consensus on any single social systems theory. After reading their works and others I have acquired more or less an intuition concerning the application of systems theory to social theory. I have made no attempt to deal with mathematical questions in this thesis.

The application of mathematics will, however, be the next step in the development of community systems science. The main systems model used here is based on Ashby’s cybernetic model. Other ideas presented are synthesized from various sources.

In the social sciences the systems approach to analysis has often been contrasted to the “conflict” model of analysis. The position presented here is that social conflict can be treated as a type of functional differentiation — functional, provided that it is accompanied by enough integration so that underlying conflict social groups can still maintain a sense of common humanity and purpose. In this way I have tried to show that systems theory is capable of answering questions the conflict model is supposed to answer. The conflict approach pays too much attention to the antithesis phase of dialectics and not enough attention to synthesis. Theoretically, the systems approach will include explanations of any social phenomena, and do so with a minimum of instrumental bias. Only the reader can judge how valuable a contribution Community Systems Science: A Paradigm for Development is to the growing body of systems science literature.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Richard Jung for his valuable contribution to my understanding of systems applications to social theory. Dr. Richard Jung, of the Department of Sociology and the Centre for Advanced Study In Theoretical Psychology, was not able to help me complete the thesis as committee chairperson.

I would like to thank Dr. David Wangler, of the Division of Community Development and the Department of Education Foundations, for his intellectual stimulation and constructive criticism throughout the thesis preparation.

Thanks also go to Dr. Ray Rink, of the Department of Electrical Engineering, for valuable guidance and feedback concerning my use of systems theory. My committee chairperson.

Dr. Regna Darnell, of the Department of Anthropology, deserves special thanks for her painstaking reviews and editing assistance. Dr. Darnell has been a source of continuous support and guidance.

I would also like to thank the staff of Petro-Canada’s Department of Environmental and Social Affairs. They provided for me a much-needed opportunity to apply systems theory to real life problems. During the summer of 1981, I wrote a report on cross cultural impact assessment for Petro-Canada. The results have been incorporated throughout this thesis and particularly in Chapter 3.2.

Very special thanks go to my wife, Lori Bissell, for her patience in seeing me through the preparation of this thesis.

0.1 Introduction

The following parts and chapters constitute an attempt to show how systems science can be applied to the study and development of human communities. By covering issues of universal, evolution, networks, development, engineering, and management, the thesis should provide new and useful insights into the nature of communities.

Community systems theory is to offer a general conceptual framework for the interpretation of any empirical observations of communities. Outlines of community universals and evolution are to guide thinking about organization and change in general. They set the stage for the application of theory in community analysis and synthesis.

In Community Systems Analysis the general theoretical framework is used to show how particular communities can be taken apart conceptually for study. In Community Systems Synthesis, the last part, the framework is used to show how communities can be created and controlled.

No definition of community is presupposed, it is argued for throughout the thesis. Using this approach, the thesis tries to convince the reader that if he/she thinks of community as an organization of various resources standing between a population and its environment, and which is changed according to the felt needs and values of the population, he/she will have a clear, distinct, and useful understanding of human community. This basic proposal is elaborated on in the second and third parts where community is the subject of analysis and synthesis. It is also argued that if one understands the nature of community organization and change, then there is a strong foundation established for community development practice. The inherent principles in communities can be exploited for intentional and rational control of development.

The six cases of communities taken from anthropological literature and used as examples for analysis were chosen to represent human communities across the globe and at different places in cultural development. They are also selected to be paired with particular networks, so in each case, the network analyzed is of some anthropological significance.

In Chapter 3.1 the design of a space colony is used to exemplify systems engineering. It is chosen because of the important role systems engineering will play in the actual design and construction of space colonies. It is also an interesting prospect as it includes such issues as the future of human community, complete design for self-sufficiency, and the use of creative imagination in community design.

In Chapter 3.2, an example of cross-cultural development between Canadian native people and fossil fuel resource development proponents is used to illustrate systems management of communities. This choice was made because of the growing frequency of cross-cultural encounters around the world. Rapid acculturation is going to continue to increase as the world’s population and communication systems increase.

1. Community Systems Theory

Community systems theory is presented here as an organized set of ideas concerning the nature and evolution of community. These ideas are abstract representations of reality, beginning with substance and form and ending with networks and development. Human community may be studied in terms of universal characteristics and their genesis in human nature. In this way community development practice may be guided by an understanding of the inherent limitations and potentialities of people vis-a-vis organizations. In other words, we should only expect people to be able to engage in a specific range of social behaviours. General systems theory will be used to enlighten traditional social theory, and this will result in a community systems theory. General systems theory is a growing body of ideas which try to explain how things, particularly living things, are organized to achieve specific organizational goals through self-regulation. Human community is like a life form in its organizational behaviour and can, therefore, be understood in terms of the concepts and principles of general systems theory. Systems theory can be used to explain universals of community organization and the principles of change involved in community evolution. When this task has been achieved, community systems theory will be applied to the analysis and synthesis of communities.

1.1 Community Universals

Community universals are those characteristics of human communities which are common to all, regardless of time or place. Communities may be understood to have causal and logical structures that function in maintaining human populations within a range of satisfactory living standards. Causal and logical processes joined together in a special way create a self-sustaining system. This system is a pattern of organization that can be seen in six different ways in any community. Semiotic, time, space, communication, material, and command networks combine to produce the substance and form in communities. It is important to identify these networks and their relationships so that balanced development takes place in a controlled manner.

1.1.1 General Universals

To speak of universals, or of elementary particles, is to speak metaphysically. There is no empirical basis for these ideas, only intuition or perhaps logic. The ideas that follow in this section may be metaphysical ideas, but they may be useful in organizing ideas which have empirical bases. If there are unchanging laws governing all behaviour and processes in the universe then it is with these laws that we should start in our pursuit of understanding of human communities.

Let us suppose that the universe consists of two things only: substance and form, and that these are embedded in time and space. Substance may be equated with energy, and form with patterned relations. In other words, form is the ordered pattern of causal influences between instances of substance. Mental information consists of representations of these patterns. With complete information all changes in pattern are fully explainable and predictable. Further, particular instances of substance may be referred to as entities, while particular instances of form will be called relationships.

Substance and form are abstract concepts which in reality are never isolated. They are always found together in organization. By definition, then, organization is a set of entities and their relationships. Organization is located in space. In the temporal dimension, entities and their relationships exhibit change. Together, organization and change create system.

As substance and form, in all their potentially infinite manifest organizations, change, it becomes evident that there are unchanging laws of change. There are essentially two kinds of change in the universe: change of substance and change of form.

The first kind of change is described by the laws of logical inference, the second, by the laws of thermodynamics, or of general causation. By the logical laws, information is transmitted. By the causal laws, energy is transformed.

There are also two general kinds of organization: organizations that control themselves, and organizations that do not. In organizations that control themselves relationships are such that they are not affected by a change in substance. The laws of logic govern the application of the laws of causation, in uncontrolled organizations, the laws of causation govern the application of the laws of logic.

Controlled organizations, governed by the laws of logic, are called open systems. This is because they are open to energy inputs from outside their bounds but are closed to information inputs. They change in substance, not in form. Uncontrolled organizations, governed by the laws of causation, are called dosed systems. They are closed to energy inputs, and they change in form, not substance. The universe as a whole is a closed system. There are apparently no inputs of energy from elsewhere. There is no empirical evidence of any god who controls the whole thing with an end to create order.

According to physical observations, (as opposed to spiritual revelations) the universe as a whole is approaching a state of maximum disorder. That is, a state in which all causal relations are equal in information — all events are destined to become randomly distributed.

Human community is a temporary isolated instance of a reversal of this trend. Like life forms, communities are open systems. In communities, causal relations become more organized and each relationship contains increasing amounts of information, provided, of course, that the community is viable. The next section will attempt to make more clear how communities are organized in relation to other open systems in general.

1.1.2 General Systems Theory

The universal characteristics of human community can be best explained by reference to those concepts and principles which have been identified as common to all open systems. General systems theory provides such a set of ideas as it defines systems as collections of inter dependent entities in a patterned formation (von Bertalanffy, 1 968). This means that a system, such as a community, consists of entities (energy) and patterned relationships (information). An open system, as mentioned earlier, is a system with inputs from its environment. It is a synthesis of two processes of change: causation and logical inference. Structure and process are two concepts that help reveal the nature of causation and logical inference and their functions in systems.

1.1. 2.1 Structure

Structure, in the sense used here, refers to the structure of change in organizations. It consists of an antecedent and a consequent, or input and output. It describes two states of an organization separated in time, in the case of causation, or separated in space, in the case of logical inference. The two constant structures in terms of which systems can be understood are the causal structure and the logical structure.

Processes governed by the laws of causation or logical inference make the changes between antecedent and consequent in a system’s structure.

All systems consist of structured change. Communities consist of energy in many forms. People, human behaviour, capital and technology, food and vegetation all contain energy. Community is a system of informed energy. One useful way of thinking about energy in all its diverse forms is through its behavioural structure. All things in the physical universe can be described in terms of energy and its alternate state, mass.

Motion, force, and electro-magnetic waves, for example, obey the law of conservation of energy. This first law of thermodynamics states that energy cannot be created or destroyed but only transformed.

All energy changes from one state to another, from an antecedent, cause, to a consequent, effect (See Figure 1). A universal condition stated in the second law of thermodynamics exists for closed systems whereby causes are more organized than effects. This is the tendency for all energy to become random , to end in a state of maximum entropy. Entropy is a measure of disorganization. As entropy (or disorganization) increases, the causal influences among entities become equal, in other words, a state of equilibrium is approached in which the information needed to predict behaviour becomes so diffusely distributed as to be practically lost. It means that there is lower probability of any particular event occurring as entropy increases.

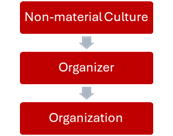

Figure 1.

Causal Structure

If an environment of a community is considered a cause , and its population an effect, the population would die without a continuous input of energy from the environment. But a community is more than a collection of energies. It is capable of maintaining a particular formation in spite of a change in energy. A community can remain essentially the same even with a complete turnover in its population. The energy that passes through the community becomes more disorganized as its information is used to support community organization. This issue concerns the need for information in the control of systems. In order to achieve and maintain its desired level of organization, a system must consume the effects of input entities by filtering them out and rearranging them to suit its needs. Once removed from the input organization, the special characteristics of these entities leave the remainder of the input less organized.

Let us assume that the universe is deterministic, but also, that we lack complete information about any particular causal event. The amount of information in any organization is at any time, constant It is a record of all simultaneous causal relationships, and must, therefore, always sum to certainty — a perfect explanation of organizational behaviour. Only incomplete knowledge of this information leads to predictions with probability of less than 1. However, when a system is highly organized, the causal relationships are controlled so that little interference occurs among entities. Highly organized systems, such as open systems, exhibit regular, or repetitive, behaviour patterns. Information needed to predict changes in behaviour is therefore more easily acquired. As systems become disorganized it becomes more difficult to get this information. Events appear to become more random or controlled by chance. Acquired information reduces our cognitive uncertainty about any organization (Orians, 1 973,349).

Where fewer causal relations are involved, more information is contained in each causal relationship. As the number of entities in an organization increases, so do the number of relationships. The total information involved is then increased, even if the individual behaviours of entities are relatively understood. In very complex organizations, where there are a large number of entities, general systems theory and simulations are needed to acquire the information required for explanation, prediction, and control. This is the case for human communities.

Human communities are complex systems. They can be more or less organized, goal-seeking, and self-regulating. An understanding of how a community works involves the identification of causal relationships. A community has its own information processing capacity which makes possible self-control, and which permits the community as whole to avoid the general trend toward increasing entropy. This information processing capacity can be explained with reference to the structure of logical inference.

The simple logical structure of information behaviour runs parallel, conceptually, to the simple causal structure of energy behaviour. Information in an antecedent, premise, is imposed on a consequent, conclusion (Figure 2). The pattern forming the premise is duplicated in the form of a conclusion. The first law of logical inference is that patterns of relationships are maintained between premise and conclusion when transferred. There is no loss of information in either premise or conclusion if there is no interference from outside the simple structure. The information need not be contained in language as it is in symbolic logic. It can be the pattern of relationships in any organization.

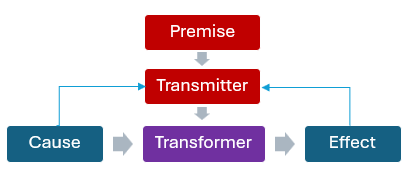

Figure 2.

Logical Structure

This logical inference structure and its associated law underlie all living forms of energy. It is required for any achievement or maintenance of higher levels of organization. However, it does not defy the second law of thermodynamics because the net effect in the structure is increased entropy. Imagine a gasoline engine burning gases to maintain its rotary pattern of output. The heat produced by combustion is only partly used to turn the engine crank. Likewise free energy flowing through a community is only partly preserved in the organization of the community. This is the second law of logical inference: logical activities create waste energy.

In a human community this logical structure exists between the minds and the physical resources and behaviours of the population. It is -essentially the same type of structure present in cell development and division. The pattern for cell development is kept in a premise known as the DNA code. It is used as the basis of the conclusion, the body of the cell. In communities and cells alike, conclusions are consistent with premises and energy is used to make the pattern transmission. The specific operations contained in

the causal and logical structures make limited and regular changes to inputs. These operations, or processes, perform organized change.

1.1. 2.2 Process

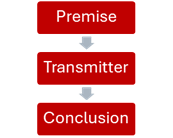

The structures of causation and logical inference contain processes best described as transducers (Ashby, 1958, 44) Transducers alter inputs according to certain laws or principles to create outputs. In the causal structure transducers, located between cause and effect, will be referred to as transformers. They change the pattern of relationships in the input energy according to the laws of causation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Causal Process

In logical structures transducers will be called transmitters, as they are located between premise and conclusion to duplicate information. They do this according to the laws of logic. Transformers lose information and conserve energy, while transmitters conserve information and lose energy (Figure 4).

Community transformers consist of all the materials and behaviours used to

convert energy into useful forms for the population’s needs (Figure 5). Transmitters are collective decision-making and problem-solving activities carried out by the population to make ideals and traditions become actual behaviours and materials (Figure 6).

The specific activities of the transformer and transmitter are parallel in that, if considered separately, both are only capable of making one kind of change, reduction. Either information is lost or energy is lost. However, if considered in combination these two structures are able to increase both energy and information within their bounds. Such a combination results in an open system.

Figure 4.

Logical Process

Figure 5.

Community Causal Process

Figure 6.

Community Logical Process

1.1. 2.3 System

If a transformer of a causal structure is operated on by the transmitter of a logical structure, an open system is created (Figure 7). The information transmitted to the transformer from the premise makes the transformer a primary conclusion. When it transforms energy from cause to effect, the effect becomes a secondary conclusion. The premise provides information which causation has lost and the cause provides energy which logical inference uses. The two structures support each other.

An open system is one that has an environmental source of energy (von Bertalanffy, 1 968,75). In this case the environment is the cause. By definition, a system has no control over its cause. It is a given. The environment of a community is defined as any arrangement of physical, biological, or social entities which have not been organized or altered by the community. The boundaries between community and environment in any particular case are difficult to define because there are degrees of control by the community. Domestic plants and animals can be considered a part of a community, whereas wild ones may not be so considered. Of course, residents are a part of it, but visitors from elsewhere are not so likely to be. The criteria used to make this distinction vary from community to community.

The result of the union of causal and logical structures is that the causal effect becomes isomorphic to the premise as the pattern originally in the cause is partially replaced by the transformer. If the information in the effect is greater than that in the cause then, except for the energy lost in the transmission, entropy has been reversed.

This means that the transformer can perform the opposite to information reduction. It acquires this ability from the logical inference structure. This new process may be called equifinality. Equifinality is the tendency to achieve a particular high level of organization regardless of initial causal conditions (von Bertalanffy, 1968,74). Such a tendency is a highly improbable one, and of course requires input energy in order to occur.

The logical inference structure also becomes capable of an opposite process as it can begin to grow in energy content. The amount of energy in the structure is not continually reduced but can accumulate because of its connection with a source. The open system is governed by the first laws of logic and causation.

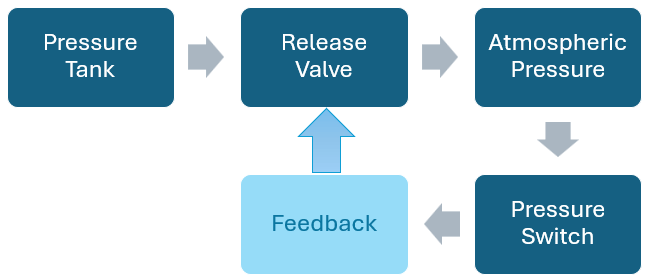

Together the two structures forming a whole system have a new pair of properties which distinguish them from their isolated states. These are equifinality and growth. But an additional process can also be created. If information can be relayed from both the causal and effect states to the transmitter, then inductive inferences can be carried out. Feedback, information from the effect to the transmitter, tells the transmitter if its message to the transformer was successful in creating a reproduction of the ideal state defined by the premise. Any discrepancy between the two results in the transmission of new information to the transformer. Thus, feedback provides a variable minor premise which alters the primary and secondary conclusions (transformer and effect).

Feedforward from the cause to the transmitter also serves as a minor premise that can alter conclusions. This feedforward makes changes in the transformer possible before changes in causal conditions effects it. It is the combined information from cause and premise, either in the effect first or directly in the transmitter, which creates mutated information that can be selected for survival. Any of this new information that becomes independent of the original premise and is embodied in an effect is a candidate for evolutionary progress. The information from original premise and cause, however combined, can become a new premise in a new system. If the combination has the ability to generate more certainty in its effects, that is, reproduce itself more reliably with the same variety of causal inputs, then the synthesis of original cause and premise will have been inductive.

This synthesis could take place between premise and cause alone. It may have happened in the most rudimentary of early systems, such as in the formation of proteins. Feedback and feedforward make this synthesis more likely and more successful because they enable a transmitter to complete the synthesis according to certain rules and criteria that may exist in the premise for such processes. The transmitter, in addition to being able to discriminate between ideal and non-ideal, is capable of analogizing. In this way the similarities between premise and feedback/ feedforward inputs can be used to create more general or abstract information. Not mere combinations of information, but higher levels of it can be formed according to certain rules called heuristics. Heuristic rules of induction are functionally similar but opposite to algorithms (logical rules) of deduction.

Heuristics are rules learned through experience of similarities among differences. They are like statistical hypotheses in that they are arrived at through induction and do not offer certainty, only probability.

As these systems have become better organized through mutation, combination and induction, they have acquired the ability to learn from information processing. They no longer depend entirely on generational changes to improve information processing abilities. By learning a system can use the minor premises taken from feedback and feedforward and use these not only in the immediate situation but store them for future use as major premises. For animals such as primates, instincts (major premises) are not used for completely determined behaviour sets but for more general types of behaviour that need to be detailed in light of what may best be described as heuristics.

In human communities learned information can be shared so that the total information available to an individual is greater than that which is instinctive or personally acquired. Induction can also be expanded even further than at the individual level, and the total environmental variety that can be reduced by the community is greatly increased (Figure 8). The non-material culture of a community consists of shared language, beliefs, and values — meaning that is derived from experience through induction guided by heuristics.

Underlying the preceding discussion is another statement of law. There has been a law of requisite variety identified to explain the success of systems. According to this law a premise and transmitter must be able to provide requisite appropriate variety to the transformer to counter any and all of the variety in the cause (Ashby, 1958, 206). The transformer must be designed by the transmitter and premise to handle the causal input variety with alterations that result in the desired effect. Informational disturbance from the cause must be minimized or eliminated if there is to be successful embodiment of ideals in the effect. In a sense then, two conclusions follow from the premises, the transformer design and the ideal effect. Each is a synthesis of energy from the cause and information from the premise. Enough energy from the cause is also needed to feed the system. Thinking and doing use energy or create waste energy.

Now these general systems concepts and principles must be applied to social systems. The following discussion will help show how general systems theory can be used to identify, describe, explain, predict, and control social phenomena.

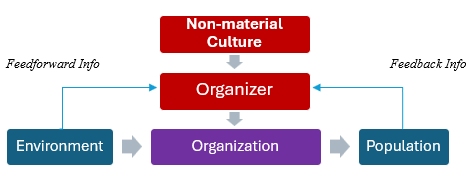

Figure 7. General System

Figure 8. Community System

1.1.3 General Social Theory

In order to find suitable subject matter for a theory of community systems, a look at the traditional breakdown of social science theory is needed.

General systems theory can be applied to the study of social science matters just as it can be applied to cells, organisms, and computers. In each case a logical structure imposes organization on a causal process and results in an effect which is relatively isomorphic to the original premise.

Traditionally the study of society, civilization, culture and institutions has been broken down into conceptual networks. Cultural ecology and economics study the flow of energy matter and money through a community or society. Human and cultural geography study the organization of people and institutions in space. Sociology studies patterns of social interaction, particularly symbolic interaction. Political science and law study the system of roles, rights and responsibilities in a community or society, particularly as these effect control of social interaction.

Anthropology is generally thought to cover all matters in a culture, however, perhaps the most significant contribution this social science has made is in the area of cognitive style or cognitive paradigms. It is in the empirical study of subjective culture that psychology has been shown by anthropology to have an important relationship to social organization. Cross-cultural psychology, as a discipline of anthropology and cognitive psychology, has begun to determine the nature of this fundamental relationship. Sociology of knowledge has also approached this issue, but primarily from a theoretical viewpoint.

Finally, history, long considered a mere record-keeping descriptive science of the past, holds the key to the study of the organization of time in a society. This view of socially organized time has yet to be accepted but the growth of futurology may provide a catalyst in the reconstruction of the traditional view of history. Futurology is the science which studies the possible sequence of events following trends shown to be developing in the present.

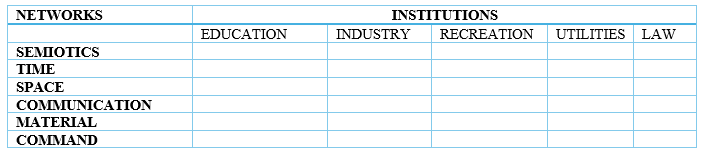

If we take the essential subject matter of these disciplines of social science a new conceptual framework can be devised which is most amenable to a community Systems theory. The following table pairs science and subject of science:

Table 1. Community Networks

| COGNITIVE ANTHROPOLOGY | SEMIOTICS |

| HISTORY | TIME |

| HUMAN GEOGRAPHY | SPACE |

| SOCIOLOGY | COMMUNICATION |

| ECONOMICS | MATTER |

| POLITICAL SCIENCE | COMMAND |

The list on the right constitutes the set of community networks. These networks can be studied in terms of the concepts and principles of general systems theory. The following sections will attempt to make clear how each network consists of processes which impose information on energy.

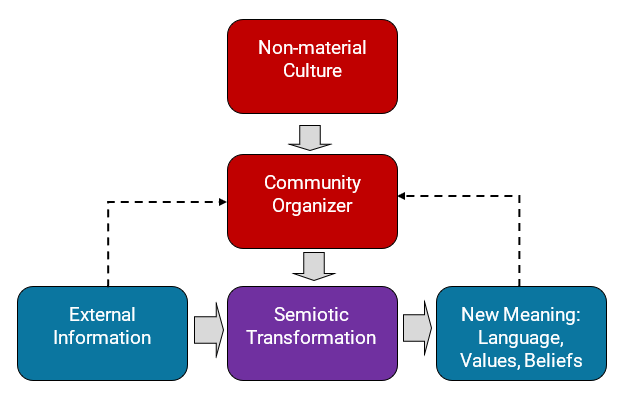

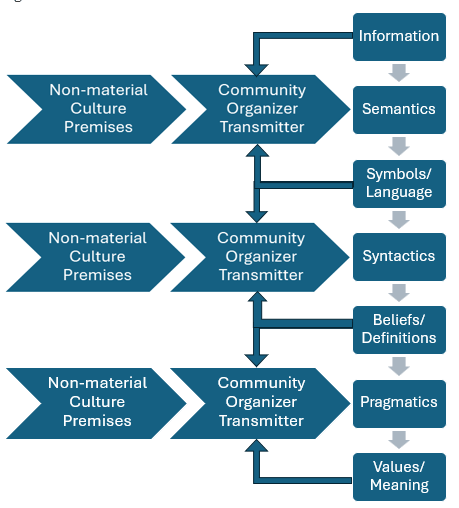

1.1. 3.1 Semiotics

The semiotic network of a community is the set of values, beliefs and symbols that are held in common by a population (Figure 9). It is also the relationships between these ideas, and the means by which they are created, altered and used. It is the collective thought, mind and identity of a population. It is a shared model of reality. Although not all ideas are equally shared, there is a coherence among ideas which unifies them. In the terminology of systems used previously, the information network makes up both premise and transmitter for each of the other networks and their integration. In this way the semiotic network is special, but it is also to be viewed as a peer or sibling to the others.

This is so because it too is partially dependent on new inputs from the community’s environment and serves personal needs inherent in the population. Computer simulations of the information networks of a community may be capable of giving an adequate representation of the complex values, beliefs, and symbols (See Chapter 3.2).

Figure 9. Semiotics

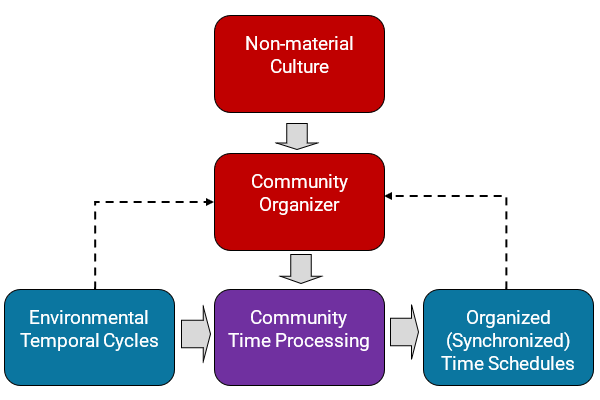

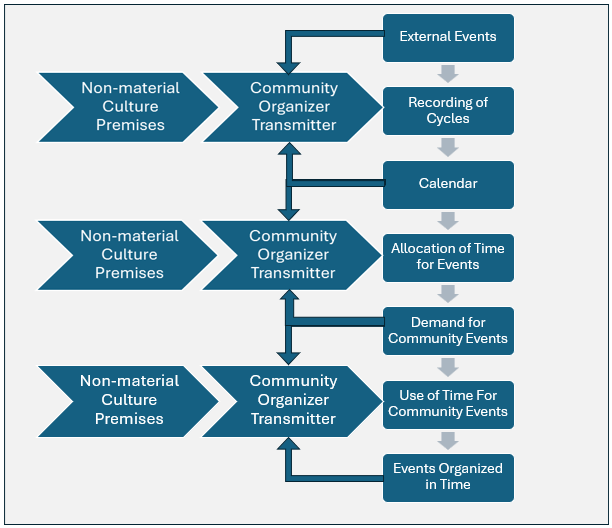

1.1. 3.2 Time

The temporal network organizes community events in a time sequence (Figure 10). It does this for the past, present and future. In each community there is some standard or set of standard units of time which are used to relate events to one another. The standard may be natural, like the positions of the sun during the day, or artificial, like the minutes and hours on a clock. In either case unscheduled time is environmental to the community, a cause which is to be given order in terms of community affairs. Organized time is necessary to satisfy human needs for predictability and regularity and for some degree of variety. Calendars and timetables are common means used to represent organized time.

Figure 10. Time

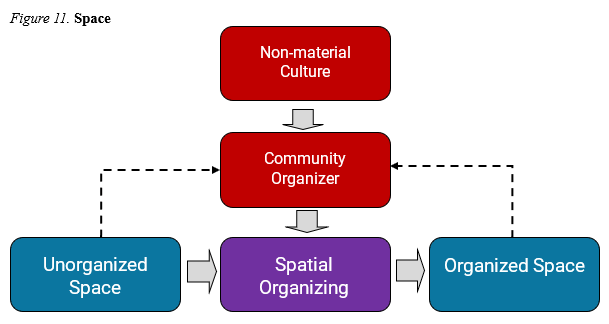

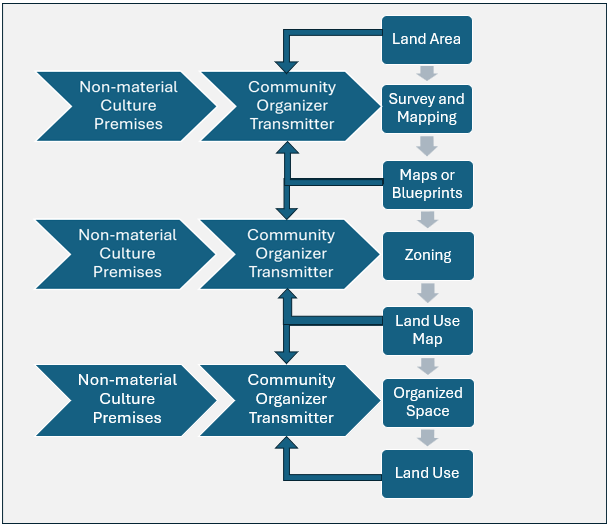

1.1. 3. 3 Space

Spatial networks deal with the organization of people and things in space (Figure 11). They determine who and what goes where. The area to be occupied is the environment for the community and it must be transformed into a pattern of subspaces designated for special purposes. Transportation routes, residential, commercial, agricultural, and industrial areas (or zones), are common categories of organized space which meet the needs of a community population. These divisions are often represented on maps and blueprints.

Figure 11. Space

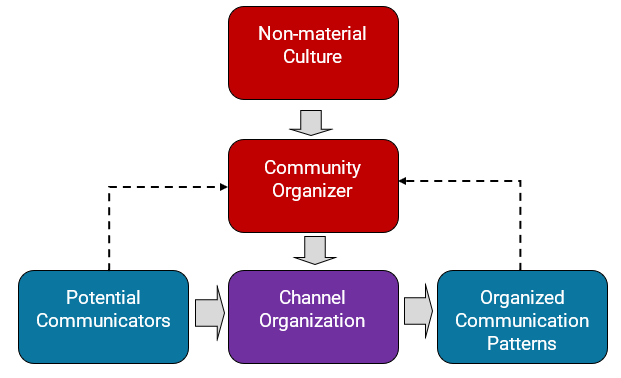

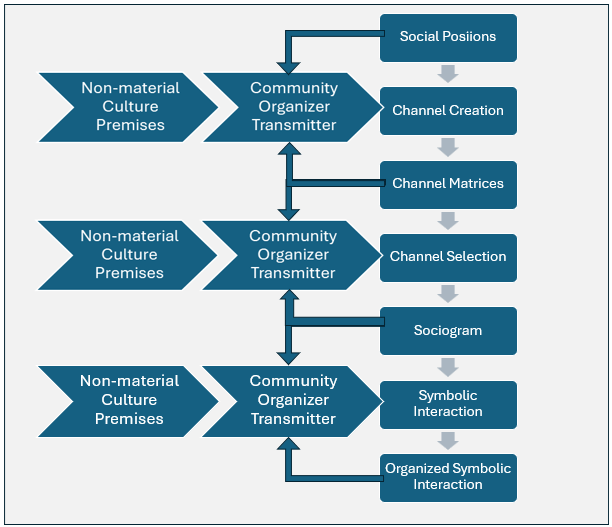

1.1. 3. 4 Communication

Communities include patterns of symbolic interaction. There is an opportunity for communication at every interpersonal contact, or among any members of the population. Only some of these possible relationships are used for this purpose. The complete set of possibilities is the environment of the communication network, and the organized pattern of symbolic interactions are selected from this set according to the needs and desires felt by the population (Figure 12). These needs and desires may be personal or institutional, informal or formal, but the means of selecting and using channels for communication are at least partly culturally determined. Sociograms, statistics and sociometrics may be used to represent the general patterns of symbolic interaction.

Figure 12. Communication

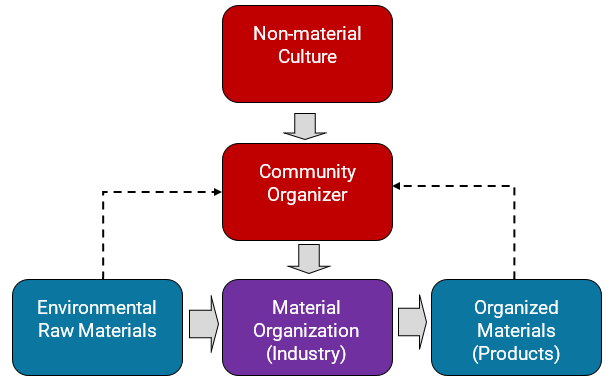

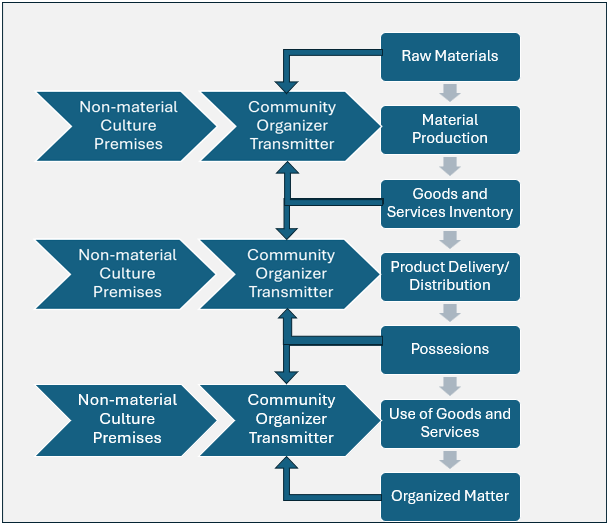

1.1.3.5 Material

The material network of a community most resembles the general model in systems theory. Although other networks operate on the same laws and principles, they modify a pre-existing pattern of energy on a different scale (Figure 13). The material network is defined in this context as the system that organizes things, not in space or time, or with respect to symbols, but concrete things- in-themselves. It transforms matter that is not useful, or is harmful to the population, and makes it useful and harmless. The material environment of this network is all things that have not previously been altered by the population. The creation and use of tools are an important part of the transformation process. Solar collectors, for example, represent a major kind of transformation. Econometrics and certain ethnographic techniques can be used to illustrate the flow of matter through a community.

Figure 13. Material Culture

1.1. 3.6 Command

In every community there are many kinds of decisions to be made concerning how people are to behave. To ensure that these decisions are made effectively for the population, a special network is required (Figure 14). The command network takes as its environment the set of all possible functional behaviours and organizes these into sets of roles to be performed by certain people. Each role with its associated rights and responsibilities is given a status in an organization of roles. Behaviour is then relatively coordinated and regular. Each person is given a set of roles and knows what to do in particular situations. At the same time each learns that the behaviour of others can be reasonably predictable. The different roles should be designed to be complementary, so that behaviours are at a minimum of conflict Hierarchical structural charts can be used to show the overall organization of roles.

If these community networks are integrated conceptually as they are concretely, a coherent theory of community systems organization results. It is important to see how the networks combine to produce a coherent goal-oriented and self-regulating community system. A discussion of this now follows.

Figure 14. Command

1.1.4 Community Systems Organization

To summarize the last few sections, a community can be thought of as a system of six networks. Semiotics, time, space, communication, matter and command are the basic parameters of any social phenomenon. In each case there is information (organization) imposed on some environmental source of energy. The result is, in most cases, a satisfaction of human needs in the population according to criteria maintained in the minds of that population.

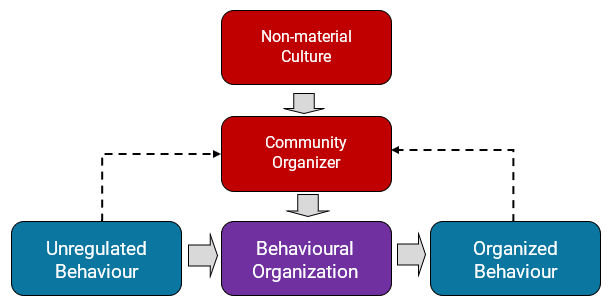

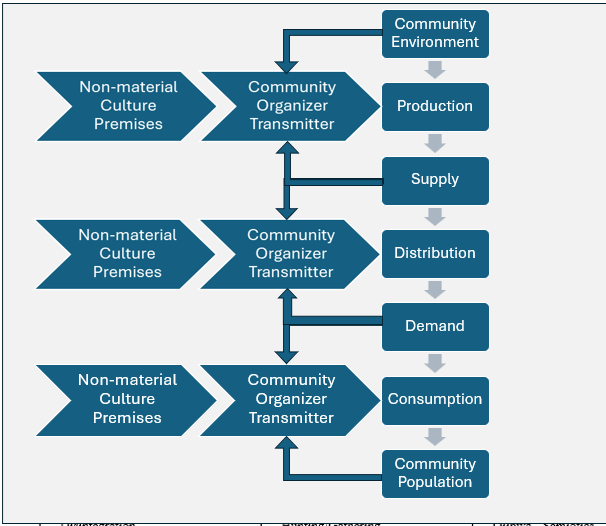

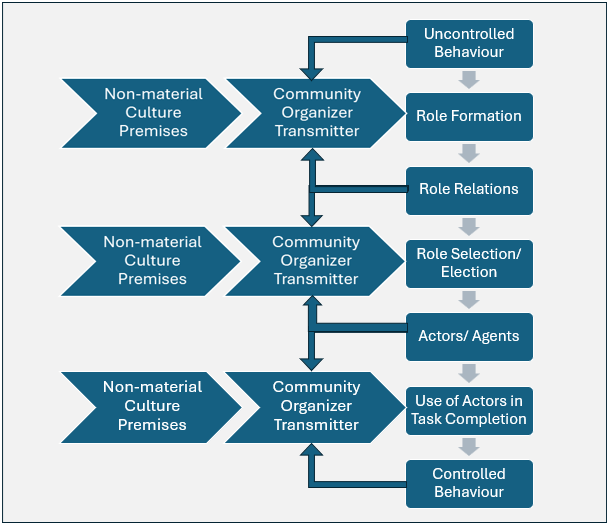

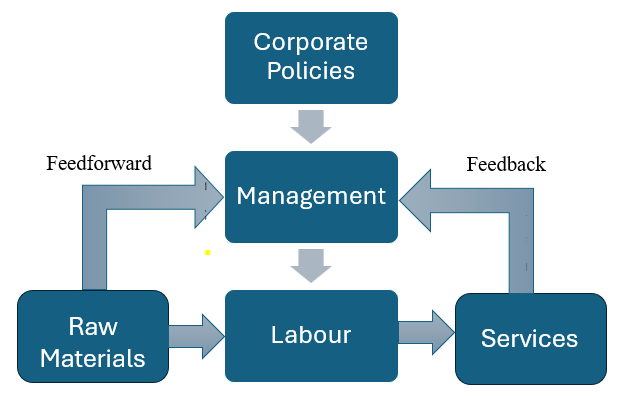

A complete definition of the general systems model in light of general social theory is now needed (Review Figure 8). The causal structure of a community system shall consist of environment (cause), community organization (transformer), and population (effect). The logical structure shall include non-material culture (premise), community organizer (transmitter), and feedforward and feedback (minor premises). The environment is the source of energy resources and disturbances which are modified by the community organization to achieve ideal population states. The ideal population states and the rules and criteria for organization are represented in non-material culture. The community organizer is informed by feedback and feedforward about the present states of the population and environment. It uses this information in combination with that from non-material culture to change the community organization until the desired feedback is received.

Since no community event, activity, or thing can exist without some consequences for each network, any community phenomenon must be defined in terms of its relationships to other phenomena in these six ‘dimensions’ of networks.

For example, a man’s behaviour while working in his yard may have consequences for each network. The semiotic network may be altered by the impact of his artistic expression conveyed in the floral arrangements. The time he spends in the yard effects the time he spends with his family and at work. The use of his yard for gardens may be against local zoning bylaws. His relationship with his wife could be strained if he does not talk with her enough. Harvesting a few vegetables could alter the local food market by changing the family buying habits. Finally, his friends may consider him with more or less respect as he becomes known as a ‘gardener’ in the status structure.

These are but an insignificant fraction of the possible consequences of such a mundane cultural activity. Yet it serves to demonstrate the interdependence of all behaviour in a community. There may be other networks as well as these six, but they are based on subjects identified by social scientists over the past couple of hundred years and seem to be very useful. Together, these six networks roughly define the scope of social science.

1.1. 4.1 Network Integration

It has been argued that community phenomena can be described in terms of their status across six dimensions. This implies that in order to create ideal phenomena in the population state the information concerning those phenomena in relation to the six networks has to be integrated. The status of a phenomenon in one network can limit its possible status in another network. Just as a full description of an object in space requires a specification of status on three dimensions, community phenomena require specification on six. Such a phenomenon could be unsatisfactory for reasons corresponding to the six networks.

The problem of integrating information about these networks is solved by either personal or interpersonal thought in the semiotic network. It is accomplished in the language and with values and beliefs that are common to all or most of the members of the population. Of course, there is also input from individuals which is not culturally determined, but the extent and style of this input are influenced by community information.

Once information about phenomena, defined in terms of the networks, is integrated, it becomes a pattern which can be implemented in community organization. In other words, the six networks composing the community organization become related to one another in a way prescribed by the non-material culture and the community organizer.

An instance of this integration is shown in the relocation of a Kung Bushmen camp. The hunters of the camp decide among themselves to move to a better location when local herds become scarce. It is the hunters who decide to move, where and when to move. Whose decisions these are is largely culturally determined for the command network. The decision to move is itself a direct involvement of the semiotic network.

Where to move and when are problems of the space and time networks. The decision is also based on the relative scarcity and abundance of energy resources, a material network concern. Finally, moving will be discussed between those who are affected by it, which involves communication. In this way a major decision is broken down to minor decisions that are to some extent predetermined by the traditions of the community.

Six different types of organizational patterns must be made to fit together without inconsistency and without conflict. Yet at the same time they must accomplish their joint tasks of making environmental inputs into ideal conditions for the population.

Usually, this process of integration is not without many initial inconsistencies and conflicts. The Bushmen, for instance, in relocating, sometimes have to decide to move before there is agreement on where to move to. Such pay-off’ decisions are by far the rule rather than the exception in network integration. They result in suboptimization of network requirements but optimization of overall community performance. This means that instead of the best solution being arrived at for each individual network, sacrifices have to be made.

Generally, decisions are made to favour those networks in which the population is approaching some critical threshold. The threshold is simply a level (or value) of development, or resources, that is either too great or too little to maintain the population. The Kung Bushmen may have to move because a lower threshold has been reached in their food supply. This would take precedence over the desire to wait until consensus has been reached on where to move to. In that case suboptimization has occurred. The fluctuating relative values could be expressed using supply and demand graphs. These graphs, established through trend analysis, show how the various network thresholds compare.

1.1. 4.2 Balanced Development

Over several generations a stable community develops fairly regular rules and criteria for meeting needs and maintaining satisfaction. As new members become a part of the population, by birth and immigration, they are taught these rules and criteria so their behaviour is fairly predictable and controllable. These rules and criteria (algorithms and heuristics) change gradually as new situations are encountered. They maintain a certain resemblance to the original and the more elementary ones. The body of information evolves so that useful values, beliefs and symbols are kept while those that are not are rejected and forgotten.

Continually the body of information grows. The rate of growth may be generally low, as in hunting and gathering communities, or great, as in industrial communities. But in order to satisfy all the needs of the population, the rate of growth should be roughly equal among the networks in the long run.

Unbalanced development can result in failure to satisfy human needs. If a very well developed network coexists with a poorly developed one, network integration can become very difficult to manage. The community as a whole has certain thresholds just as the networks have. The important thresholds for the whole community concern attention to the network thresholds. As unbalanced development increases, and becomes more complex, it becomes more difficult for residents to be sensitive to, or aware of, network thresholds. Short term attention to underdeveloped networks may be necessary.

In advanced industrial societies, communities have well developed material networks. However, their semiotic networks have not progressed at the same rate. Information has proliferated but no equally major change has occurred in information organization. Perhaps the use of advanced computers and telecommunications can help rectify the problem to some extent, but a new way of thinking is needed. General systems thinking can play an important role in organizing information, as it is interdisciplinary and is capable of integrating the progressively more specialized information caused by the industrial revolution.

In the long run, cultural evolution can resolve these kinds of imbalances. But, if communities are sufficiently understood, balanced development can be built in and continually managed. This does, however, require some holistic perspective such as use of general systems theory. Using community systems theory, community development practitioners can gain some rational control over cultural evolution and use the inherent principles of change to control development.

1.1. 4.3 Summary

In summarizing this first chapter, communities consist of a causal structure and a logical structure in an interdependent relationship. This system structure can be seen in six different ways in a community; in semiotics, time, space, communication, material, and command. It is important that one or more of these networks do not get overdeveloped while others are underdeveloped, as this leads to the failure of the community to meet human needs. To understand how evolution has managed the development of communities, an investigation of theory on the psychological, social, and ecological foundations of community is in order.

1.2 Community Evolution

If community development practitioners are to help communities acquire self-control, it is important that they understand why communities exist and how they have evolved. Community development may be thought of as the ‘fine tuning’ of community evolution. The principles of change inherent in evolution are to be applied in development

The theory of evolution of human community concerns the progressive selection of life forms that are able to handle greater variety and complexity in their environments while maintaining adequate levels of need satisfaction and reproduction. Evolution is the result of the law of requisite variety. Life forms with greater capacity to respond to environmental variety, in relation to their variety of needs, survive those with less capacity. Each progressive level of organization of life forms, from amoeba to man, represents an improvement in the ability of individual ”species” to identify and adapt to its environment for self-preservation and reproduction. The information capacities of life forms increases through evolution. Human community, like a life form, is built upon the abilities of its constituent subsystems. In communities, the subsystems are people and institutions. Their abilities are used to preserve the community and its population. Human populations making up communities consist of the collective needs and abilities of individual persons. Inherent in these persons are the capacity and preference for social interaction. This makes community organization possible. The shape of community as it has evolved is also dependent on the ecosystems in which human populations exist. In brief, community has evolved as an intermediary device of human populations for protection from and exploitation of their environments.

1.2.1 Information

Human communities are made up of subsystems which are in some ways similar and in some ways different. How these similarities and differences are organized will determine the information capacity of the community. In other words, how the similar and different needs and resources of a population are ordered determines the success of community resources in turning useless and harmful environmental elements into useful and harmless factors for need satisfaction. The ability of a community to identify and use valuable naturally occurring elements also rests on this information capacity. Over tens of thousands of years of evolution, human communities have improved in their capacities of identification and adaptation. This evolution is partly genetic and partly cultural.

Essentially, what the community must be able to do is determine if a particular environmental element is directly useful to its population. If it is identified as useful, then it is used as is’, when and where it is needed. If the element is not useful “as is”, the community must be able to adapt either the element or its population’s need so that the element becomes useful, or at least harmless. Information processing required in this task is done by the community organizer. The organizer must be able to compare environmental and populations states, and, using value criteria provided by non-material culture, decide what to do. It must be able to apply the laws of logic to organizational information.

1. 2.1.1 Differentiation

According to the law of requisite variety, the greater the number of things a system can identify and adapt to, the greater is its chance of survival and reproduction. It takes a lot of variety in a system to properly deal with the vast information in an ecosystem. Micro-organisms and insects, for instance, are relatively simple life forms, yet they thrive just about anywhere on earth. They do this for essentially two reasons: they mutate easily and they are very prolific. The information needed to reduce the variety of destructive things and events in the environment is contained not in individuals but in the population. The population generates enough different kinds of individuals that surely some of them will be properly designed to survive the conditions and reproduce their own strain.

Human beings, however different they may be from one another, are capable of acquiring a vast amount of information and skill from experience. In fact, they have to learn in order to survive; there are few built-in detailed programs for survival. In addition, the reproductive rate for humans is very low compared to other species. Instead of proliferating, people have very general programs built in genetically which cause relatively extensive dependence on learning about environmental conditions, identifying objects and events and responding appropriately for survival.

Whether insects or human are considered matters little when referring to evolutionary principles. Natural selection favours those life forms which have more information appropriate to their needs in relation to their environments. Reproductive and mutation rates and individual learning are two means of acquiring and using the needed information. Another means is cooperative interaction. Individuals who separately do not have the requisite variety of abilities can pool their resources to meet their needs. The most elementary of these cooperative interactions is sexual intercourse for reproduction. Reproduction is a mutual need for both sexes which can only be achieved, in most life forms, by cooperative interaction. Information from both parents is synthesized to form new original offspring. In human communities, personal interactions have become differentiated into the six networks outlined in the first chapter. These networks become further differentiated culturally into institutional subsystems. Each network and each institution serves a special function in the community. This is how communities increase their information capacities.

1. 2.1.2 Integration

The fundamental pattern underlying these different ways of getting and using requisite information is the integration of differentiated units. In each case different abilities are united and coordinated by a common body. In insects the variety provided by mutation is controlled by genetic structures themselves, which in essence are similar between individuals of a species. In sexual reproduction, different sets of genes are united according to the common basic structure of each. Learning processes, including identification and adaptation, involve the use of basic mental faculties and behavioural potentials to integrate different ideas and behaviours. In other words, differences are managed by similarities.

The function of integration is not to reduce the negative impacts of environmental influences or to increase positive impacts, but to control the different activities that fulfill these tasks. It performs conflict-resolution through self-regulation and goal-orientation. Because of this, the system that integrates differences has less information than is contained in those differences, but more information that is common to them. It only needs to be able to identify and adapt to the similarities among the differences. It has a general overview of network and institutional subsystem relations ■ 31 and their overall goals.

In order to coordinate the actions of the differentiated subsystems and to fulfill their individual and common needs with their individual and common resources, the integrating system must weigh the costs and benefits of the various ways of combining subsystem actions in achieving the goals. On the one hand there is a common goal to be optimal, and on the other, competing needs of complementary subsystems.

This task of integrating different complementary subsystems is needed anywhere there are substantial conflicts operating. While one integrator works to coordinate its subsystems, other integrators do likewise. Then these different integrating systems performing different integrations need to be integrated. Systems performing integration at this level also need integrating. A hierarchy of systems controlling other subsystems emerges, with the end result being an extremely complex system of subsystems integrating different subsystems (Parsons, 1977). Conflicts at one level are resolved at the next higher level. If the hierarchy is relatively flat, with a higher degree of differentiation than integration, it is relatively flexible and effective in meeting various needs. If it is relatively high and narrow, in other words, has relatively greater integration in relation to differentiation, then it is more stable and efficient in the use of resources.

1.2.1. 3 Process of Community Organization

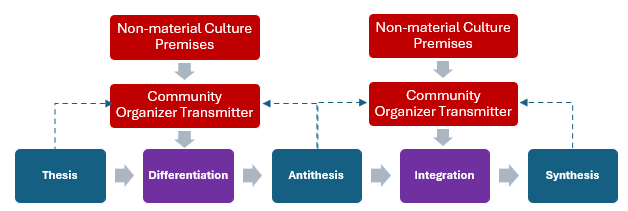

In summary of the last three sections, it may be said that the process of community organization consists of two sub-processes: differentiation and integration. These two processes are common to all evolved organization. The increase in complexity is one measure of evolutionary advancement. That is, the more complex the organization, the further it is down the road of evolution. Using the language of dialectics, an organizational scheme may be offered to show the relationship of differentiation and integration to change (Figure 15.).

In this figure, an original state, thesis, is differentiated into separate antitheses which are in some way functionally complementary but also in conflict or competition. The antitheses are then integrated so that a synthesis results, which has the advantages of specialization but not the problems.

Community organization has evolved as networks and institutions have become more differentiated and integrated through time. Human community emerges out of patterned interactions in which human resources (abilities) are coordinated to satisfy human needs.

Figure 15. Community Dialectics

In terms of conflict analysis, social conflict may be considered a process of differentiation.

1.2.1. 4 Community in the Chain of Being

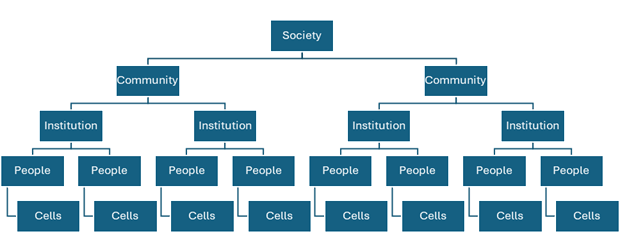

The hierarchy of systems which results from continuous evolution and increasing organized complexity can be described as a chain of being (Lovejoy, 1960). This chain appears as a static structure at any given time (Figure 16). Communities are subsystems of societies, while institutions are subsystems of communities. Institutions are made up of people, Between cells and people lies a whole range of organizations, such as organs and tissues.

Figure 16. Chain Of Being Community

On the scale of life forms there is also an organized chain of being. Some of the distinguishing landmarks of evolutionary development along this chain are as follows:

| 1 | cell reproduction |

| 2 | photosynthesis |

| 3 | herbivores |

| 4 | mobility |

| 5 | locomotion and ingestion |

| 6 | sensory systems |

| 7 | predation |

| 8 | remote senses |

| 9 | internal senses |

| 10 | central nervous system |

| 11 | land adaptations |

| 12 | learning and memory |

| 13 | mental mapping and modeling |

| 14 | abstract reasoning |

| 15 | family bonding and interdependence |

| 16 | imitative behaviour |

| 17 | cross modal transfer of learning (sensory motor) |

| 18 | symbolic communication |

These steps of development identified by Hagman (1982) do not necessarily follow the order given. The list does, however, roughly describe the sequence of developments leading to homo sapiens as he exists today. The increasing specialization of cells for specific purposes is a kind of defined differentiation while their coexistence in single organisms constitutes an instance of integration. With each newly acquired ability, previous abilities may remain but are adapted to the newcomer through the process of integration. Humans have reduced sense of smell as sight has improved. Some abilities are lost as others become more useful. Animals cannot photosynthesize. Land animals cannot take oxygen from water.

One important shift in importance is that learning and memory have replaced many functions previously performed by instinct. As a result of this and the supplementing of personal experience with cultural information (made possible by communication), cultural evolution may begin to supplant biological evolution. Survival depends more and more on acquisition and application of cultural values and beliefs rather than on inherent sensory-motor patterns. These inherent sensory-motor patterns in man are sufficiently general as to apply to the learning of any insights or skills needed for survival in any environment. What we lack in biological inheritance can be made up for by technology. In fact there is concern in some quarters that this trend will facilitate artificial support for a decaying human gene pool. More and more people are reproducing who would not normally survive under purely biological natural selection processes. This means that culture must compensate for these possible biological changes. People must become more cooperative.

1.2.2 Individual Organization

Human communities are made up of sets of individual persons and their relationships. The set of individuals, population, includes people with many similarities and differences. These individual differences and similarities are partly genetically and partly environmentally determined. Either way these can be used to define the potentials and limitations of community. Two important types of ability are important to both individual and community survival: identification and adaptation. Needs are represented between identification and adaptation and serve essentially a goal-orientation function for the individual.

1.2.2.1 Individual Abilities

Identification and adaptation are complementary. They enable a person to construct a model of reality, decide what appropriate action to take, and then act out the prescribed behaviour. The mental faculties composing the identifying system are sensory-perception, cognition, memory, and motivation. They interact to produce a model of reality and to prescribe action (Heimstra and Ellingstad, 1972). The model is a pattern contained in the central nervous system. The pattern is relatively isomorphic to reality. The behavioural capacities making up the adaptive system include reflex, instinctive, conditioned and intentional patterns. These combined behavioural patterns can be used to generate a wide range of appropriate responses to environmental stimuli and inner drives.

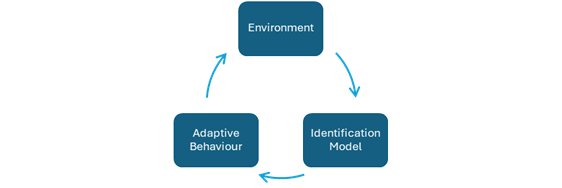

Together these two systems in an environment form a special feedback loop. An empirical modification cycle exists whereby information from the environment (empirical knowledge) is organized into a model of reality which is used to determine behaviour and change the environment (Laughlin and d’Aquili, 1974, 84). New information acquired as a result of the behaviour modifies the model. This new information is feedback. If it reinforces the original model the feedback is negative, because it inhibits change. If it alters the model, it is positive, because it promotes directed change (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Empirical Modification Cycle

This process is important for human communities because it is a process that people must do together to coordinate community organization. People must have a certain degree of agreement among their models of reality if they are to agree on how to use environmental and human resources to satisfy population needs. Consequently, it is important to understand the rules and criteria used in the cycle of empirical modification.

1. 2.2.2 Individual Needs

Once a model of reality is established, emotive responses to it determine what adaptive action will take place. The emotive responses are based on human needs. These needs are, categorically, for physical, cognitive, and social fulfillment. They are instinctive, fundamentally, but each person defines his needs in terms of his model of reality, and that is influenced by culture.

If individuals are to coordinate their interactions in community organization, they must be able to agree on common needs. They must, therefore, have a similar understanding of reality and be able to communicate that similarity. Felt needs among individuals is the driving force of adaptive community behaviour. The need to achieve and maintain a certain level of basic satisfaction motivates the empirical modification cycle. Needs and abilities are components in a process for turning information in an individual’s environment into a meaningful mental model. Then the model is used to change the information contained in the environment.

1. 2.2.3 Information Processing

It has been suggested that the human mind thinks empirically in terms of space-time and causality. Information received from the environment is given meaning in terms of two innate templates (Stich, 1975). The first template organizes the information into a coherent space-time model. Spatio-temporal relations are identified so that discrete objects and events can be isolated perceptually and conceptually. The second template organizes these objects and events in terms of their causal relationships. It identifies causes and their effects (Laughlin and d’Aquili, 1974). Although this question of innate templates has not been solved, it is difficult to imagine how a new born baby would begin to make sense of anything unless he were born with some similar presumption or predisposition.

Through a hierarchy of integrating subsystems such relationships are abstracted to higher and higher levels, from pure perception to pure conception. Each time information is abstracted from perception, the original images diminish, and they are eventually lost from consciousness. In order to keep these abstractions an artificial pattern must be imposed on new perceptual substance. These new creations are symbols. They may be auditory, visual or tactile, even olfactory. The original information, however, is some how maintained in and between symbols. The process of symbolizing is called semantics. Spatio-temporal and causal relationships become represented by grammar and syntax.

The result is a continuous deep structure underlying perception and language which is common to all people, and a surface structure for each person which depends on how deep structure is applied to experience.1 When symbolic information contained in the model of reality is evaluated in relation to felt needs, and for prescription of behaviour, p rag mat i c processing has taken place. This means that the information processing function of an individual consists of semantics, syntactics, and pragmatics. More about this will be explained in the next chapter under Semiotic Network.

1.2. 2. 4 Individuals in Community

The sharing of a set of symbols and their use in language is a fundamental necessity for human community. Communication by use of gesture is not adequate for abstract thought. Without agreement on some of the more meaningful ideas about reality community populations could only organize for simple tasks.

Another characteristic of human ability with consequences for community is sheer mental capacity. The amount of information an individual can process and organize certainly defines the range of his abilities in social interaction. The limitations and potentials of identification and adaptation suggest certain natural social role capacities in community organization. For example, there is likely some optimal range of integration functions that a manager can handle. Outside of this range, dissonance, in the forms of anxiety, depression, or hostility, may be experienced, and community integration is then poorly performed.

Individual differences in abilities also play an important role in community. It is the populations’ set of individual differences that adds to the information capacity of a community. The collective variety of identification and adaptation abilities makes community a much more viable form of existence than isolation.

Genetic differences in individual abilities, if properly integrated, may be very complementary and mutually beneficial for interacting participants. Genetic similarities, represented by the universal components of mental faculties and behavioural patterns, become differentiated through individual applications to experience. So, whether abilities in mechanics, language, arithmetic or interpersonal relations are involved, or knowledge and skills in general problem-solving, people who participate in community are better able to satisfy their needs. They can draw on the resources of others as well as their own.

Community is more than the sum of the needs and resources of its population. Organized patterns of relationships among individuals are also crucial. These relationships ensure that shared resources are used effectively and efficiently to satisfy common needs. Also, the knowledge and skills which are at the base of abilities, can be transferred to other individuals without much loss. Simultaneously, community provides specialized services and goods as well as the knowledge and skills to perform and create them. That is, both energy and information are shared.

There are, of course, limits and potentials of individuals to participate in social interaction. These again are founded in biological human nature.

1.2.3 The Social Nature of Humanity

If man was not inherently a social animal it is not likely that he would learn to become one. Competition is the first rule of natural selection in evolution. Life forms which are best suited to their environment survive those which are less appropriate. A basic strategy for survival such as community or isolation could not be left up to individuals to decide after experience had shown them the costs and benefits of each. This is particularly true of man as the period of childhood dependency is so long that some instinctive drive for child care is necessary. It is also likely that because of intergroup competition, the capacity and even preference for association with groups larger than families became a part of human nature. Language learning, which seems to be an innate potential for man, serves as a vital group support mechanism, facilitating the exchange of information and meaning. Social man is superior to asocial man because of his ability to draw on the resources of others. He has, therefore been selected by nature through competition (Wilson, 1978).

Inherent potentials and limitations for social interdependence rest on these three evolutionary developments: family bonds, cooperation and reciprocal altruism, and language. They have evolved because they serve the human community in defense, offense, and territoriality (Lorenz, in Caplan, 1978). These latter three functions were the grounds on which natural selection took its toll. Groups can defend themselves against attacks and predators better than individuals can. They are also more successful at attacking and hunting. Because ecological niches are only capable of supporting a certain density of population, competition for territory will likely favour larger groups against smaller ones in expansionist feuds and wars.

1.2.3.1 Family Bonds

As organisms evolved greater capacity to learn individually, a simultaneous need for teachers and protector-providers evolved. The long period of human infant dependency needed for learning all the things for which other animals depend on instinct. 40 reflex and conditioning, demands not only a mother s presence but a father s. Mother and child must be naturally compelled to be together. Mothers inclined to neglect their babies could not reproduce their kind. But because the young require so much attention, a father must also be present to protect and provide for both mother and children. Not only this, but siblings must have some potential to learn to stop short of killing each other, because any sibling inclined to seriously injure or “kill another essentially threatens his own gene pool.

Experiments in social psychology have shown that people are attracted to others who are similar to themselves (Baron, Byrne and Griffitt, 1971, 40). They also show that eye contact and smiling are correlated with development or enhancement of attraction. Parent-child bonds and marriage bonds seem to depend on eye contact and smiling, or other perceptual cues for reinforcement. It could be that personal identity is extended to others through these gestures, and that the identification is based on perceived similarity. It is likely that a modified process of imprinting, such as that which occurs in birds, occurs also in humans. There is a predisposition to identify with parts of one’s experience which have certain characteristics common to human appearance and action.

It is a tendency to extend the self to others of a similar nature. This disposition would constitute inborn knowledge inherited along with all the other mental and physical abilities that make survival easier (Laughlin and d’Aquili, 1974, 79).